Smart cities for president? Two ex-mayors could take the movement national

Over the past decade, few philosophies have dominated local government in the United States as much as the “smart city” movement, in which mayors and their underlings have replaced traditional brick-and-mortar civic services and infrastructure with data-driven processes and information-gobbling devices in an effort to become more safe, sustainable and efficient.

And while there’s still no firm definition for what a “smart city” is — most attempts include a mishmash of gadgets, data sets and evidence-based policymaking — the idea could be on the cusp of getting its biggest boost yet, through the presidential campaigns of several former mayors who attempted to embody it during their stints running cities ranging in size from 100,000 residents to more than 8 million. The election of one of these former mayors to the White House could set up the federal government for what researchers, former and current mayors say would be a new era of empowerment for cities, and a chance to prepare for an inevitable tech-centric future.

With just four days before the Iowa caucus, only former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg remain in the race for the Democratic Party’s nomination. But both their candidacies rest largely on how they led their respective cities.

Buttigieg, 38, developed data-driven programs like SBStat — a performance management dashboard that tracked city functions like utilities, fire and police — to glean insights into how well services were being delivered. His presidential campaign’s “Douglass plan,” focusing on black communities, promises to use data analysis to reduce racial bias in health care, and his infrastructure plan would create a “21st-century public health data system” to track threats like climate change and infectious disease. The campaign would also create a federal database to document the use of force by police.

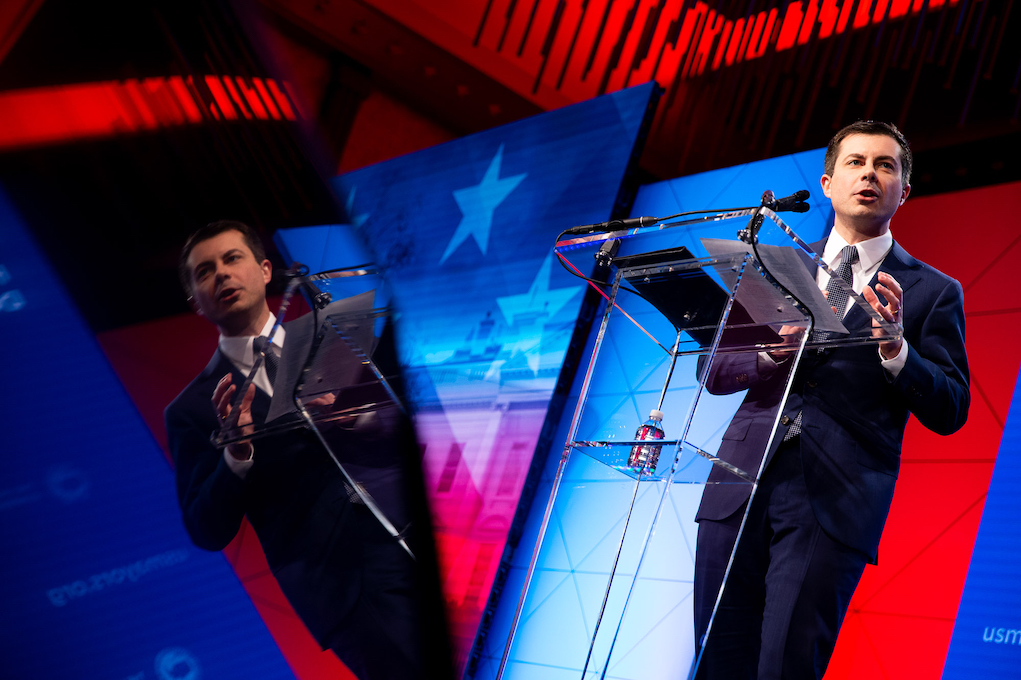

Former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg. (U.S. Conference of Mayors / Flickr)

Most of the other former mayors who’ve taken a shot at the 2020 Democratic nomination also sold themselves as savvy technocrats, including Cory Booker of Newark, New Jersey; Joaquin Castro of San Antonio, Texas; and John Hickenlooper of Denver. (Bernie Sanders, a former mayor of Burlington, Vermont, has confessed to a bit of a Luddite streak.)

Then there’s Bloomberg. The former New York mayor didn’t just govern as one of the smart-city movement’s biggest exemplars, he’s become perhaps its leading benefactor. Bloomberg, whose financial-media empire has helped him amass a net worth of nearly $60 billion, has spent more than a decade expanding and bankrolling the growth of self-identifying “smart cities” through his Bloomberg Philanthropies foundation.

The upshot of all these investments — Bloomberg-supported and otherwise — has been an accumulation of devices and data in cities everywhere, but with little federal guidance on how those technologies can be best used to make policy. But, veterans of the smart-cities field say, a president who came from the movement might be able to scale it to a national level.

A new Wild West

Since launching its Cities of Service campaign in 2009, Bloomberg Philanthropies has given out more than $350 million to in grants to promote technical, data-driven projects in cities globally. The foundation has become the largest city-dedicated philanthropic organization in the world over the past decade, fueling the desire of city officials to gather useful and potentially lucrative public data, and a private industry selling software, gadgets and environmental sensors projected to be worth $256 billion within the next five years.

While many officials concede the “smart city” label is a sales tactic, it’s here to stay, said Genie Birch, co-director of the University of Pennsylvania Institute for Urban Research.

“It’s going to happen anyway, quite frankly,” Birch told StateScoop. “It’s happening anyway, and it’s happening willy-nilly and it’s the Wild West out there. You’d rather not be the Wild West, you’d rather have transparency and accountability and so forth.”

There’s been less progress at the national level, though. While the Trump administration releases a federal data strategy annually, there’s virtually no federal regulation in place to oversee emerging technologies, like facial recognition, autonomous vehicles or the many environmental and safety sensors that cities are deploying.

But, according to Birch, the election of either Bloomberg and Buttigieg would present the federal government with a chance to establish national data standards that would both increase transparency between different layers of government and ensure that cities could compare and share data in commonly-held metrics. Birch says such a framework would be a chance to tame that “Wild West” of civic data.

In Birch’s view, a national framework for civic data would include standards for data collection and storage in virtually all areas of governance that “smart cities” agendas touch, including service delivery, transportation, social services, education, housing and tourism.

“The role of the national government here can be in the setting of standards,” Birch said. “There are all sorts of sensors out there that give you different kinds of information. It’s not going to be comparable, and you’re not going to be able to make national or sub-national decisions without having some sort of comparability among the data.”

Funding could be supplied to local governments interested in upgrading their data-collecting devices or software after the standards have been set, Birch said, much like how the Clean Water Act authorized a revolving fund for towns to build their own wastewater treatment plants. That funding structure, she said, would give cities just starting out with “smart technology” the biggest boosts, allowing them to access troves of data already collected and cleaned by other smart cities.

‘Always about smart cities’

In a speech last week to the U.S. Conference of Mayors, Bloomberg said his White House would do many of the things Birch hinted at. Touting a $1 trillion infrastructure plan, he said his administration would create a public-private consortium built around data and analytics.

“A lot of times, the private sector has a lot of information that would be good for us to have, for cities in particular,” said Janette Sadik-Khan, who led the New York City Department of Transportation under Bloomberg and is now a senior adviser to his campaign. “In a lot of instances, cities are literally planning blind because they don’t have that information. Mike’s plan will not only create a consortium to set those data standards, but create some standards for sharing that data.”

Bloomberg was “always about smart cities” during his 12 years as mayor, Sadik-Khan said. In 2007, he created the PlaNYC program to improve environmental outcomes around the city, and in 2012 signed a law requiring city agencies to publish all public data online.

But it’s Bloomberg’s financial contributions to other cities that have done the most to boost his smart-city wattage. More than 20 mayors around the country — many of whom have been on the receiving end of Bloomberg Philanthropies grants — have signed on as surrogates and co-chairs of his campaign, like Adrian Perkins of Shreveport, Louisiana, who recently said a Bloomberg presidency could empower cities everywhere.

“The only thing you have to do is actually empower mayors with resources to roll [technology] out,” Perkins said after Bloomberg’s speech at the Conference of Mayors event. “Everything about his track record speaks to that, making sure those resources get down to the local level, and allow local people to build out the cities that they want. And we all know technology has to be a part of that.”

‘Never had a president like this’

Another mayor who got a Bloomberg bump is Pete Buttigieg, with a $1 million What Works Cities grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies in 2018 to improve transportation for low-income workers in South Bend. Buttigieg’s SBStat program was also developed in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies, when South Bend was named as one of the first recipients of Bloomberg’s What Works Cities fund.

SBStat’s roots, though, lie in another city’s initiative launched long before Bloomberg got in the mayor-backing business: CitiStat, the performance-management platform Baltimore created in 2000 under then-Mayor Martin O’Malley. In an interview with StateScoop, O’Malley said programs like CitiStat create an “ability for the command staff to synthesize the latest emerging information” coming out of various government operations.

Such programs don’t always scale well. O’Malley repurposed CitiStat as StateStat when he served as governor of Maryland, but it was killed in 2015 after current Gov. Larry Hogan took office.

In both Bloomberg and Buttigieg, though, O’Malley — who was an also-ran in the 2016 Democratic primary — said he sees an opportunity to enact an agenda that leverages devices and data on an unprecedented level. The catch, he said, is that a “smart” president will have to sell the country on how those technologies can be used constructively and accountably.

“[We have to] show every citizen what we’re doing, when, where we’re doing it and whether or not it’s working,” O’Malley said. “[Geospatial information systems] and the [internet of things]” — two terms that appear often in smart-city plans — “aren’t new tools, but most people in public administration haven’t figured them out.”

A president fluent in explaining new civic technologies, data analytics and other emerging tools that cities have used to try to modernize themselves would be a first, he said.

“We’ve never had a president operate our government like this before,” O’Malley said.