States’ spending on election security expected to pick up in 2019

States and territories spent just 8 percent of the $380 million in federal election-security grants in the six months after they were distributed last year, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. But in a report Thursday, the commission said it expects the bulk of that funding to be spent before the 2020 presidential election.

The report follows states’ spending on new voting equipment, cybersecurity resources and personnel between last April and Sept. 30, when the federal government’s 2018 fiscal year ended. But the EAC said it expects spending to pick up this year as more grant money is transferred to states and as legislatures approve spending plans.

“There hasn’t been a lot of money spent, but there is a lot of activity,” Mark Abbott, the commission’s grants director, told StateScoop.

Of the $31.4 million states spent through last September, more than half — $18.3 million — went toward cybersecurity, including hiring new personnel dedicated to network security, implementing risk assessments and vulnerability scans and putting up stronger firewalls around statewide voter registration systems, which were infamously targeted by Russian hackers during the 2016 presidential election.

Rhode Island, for instance, purchased a new encrypted platform for its voter registration database, along with security tools that conduct real-time monitoring for cyberthreats and can quarantine devices if abnormalities are detected. Delaware, using much of its $3 million grant as a down payment on new voting machines, also plans to migrate its voter registration database from an aging mainframe to a cloud provider.

Several states, including Colorado, Iowa and New Jersey, are funding tabletop exercises for county election administrators, simulating cyberattacks against their offices. (The Department of Homeland Security held a national exercise for secretaries of state and statewide election directors last summer.)

Others, like New Mexico and North Carolina, are hiring information security officers tasked specifically with focusing on elections.

States and territories disclosed their full plans for the grants last August, and while the plans cover a five-year period, the EAC expects most of the money to be spent within the next 18 months and 60 percent of it spent by the 2020 election. Much of that spending will come in the form of state governments distributing sub-grants to individual counties and other jurisdictions that administer elections directly. There are about 8,000 distinct election jurisdictions throughout the United States.

Many of the local grants will be used to help small counties, which generally lack robust information technology resources, to beef up the information security around their electronic pollbooks, election-night reporting systems and websites that feature information for voters.

Texas and New York are embarking on what Abbott described as a “mammoth exercise” to conduct cybersecurity assessments for all of their counties, many of which are small, rural and lacking IT resources. Texas’ 254 counties range in size from Harris, home to Houston and a population of 4.7 million, to Loving, which is home to 134 people in the state’s far northwest corner.

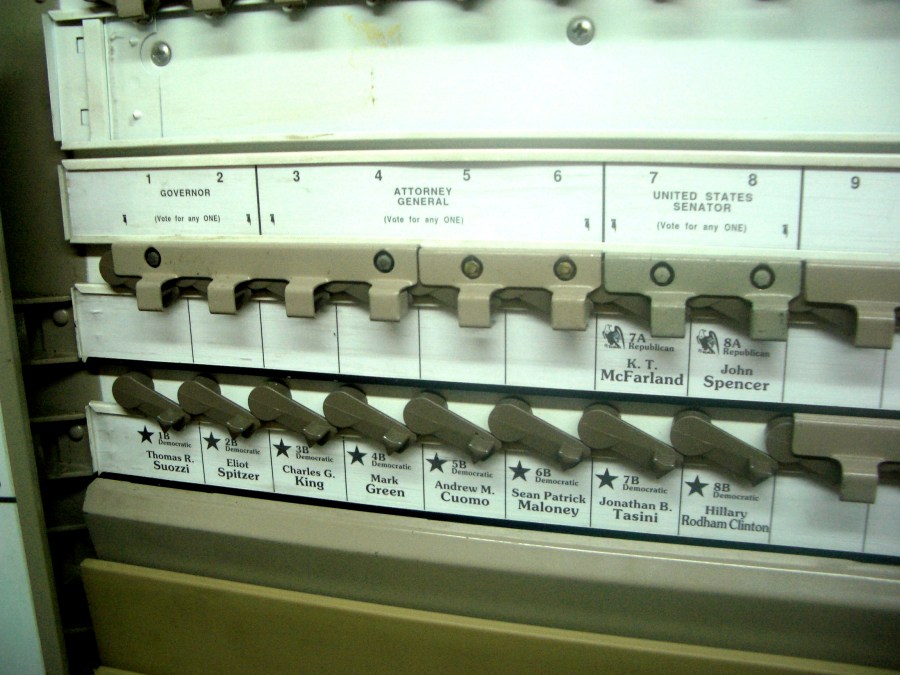

A slower moving project is the acquisition of new voting machines to replace equipment that in many states is more than a decade old. The costs of replacing voting machines faced by states is also far greater than the grants they received. Pennsylvania plans to use 100 percent of its $13.5 million grant to phase out its inventory, which is currently dominated by paperless touchscreen devices frequently criticized by voting-security advocates. While about one-third of the state’s 67 counties have started replacing their systems ahead of 2020, Pennsylvania estimates a full statewide replacement will cost at least $125 million.

But in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, replacing voting machines is a lengthy process that might not align with the timetable of the next presidential election. Procurement, which is ultimately done at the jurisdictional level, can take up to a year, and should be followed by testing to ensure the reliability and authenticity of the equipment.

“If they haven’t started the procurement process, it’s unlikely new equipment will be in place by 2020,” Abbott said.