Five state tech stories that made 2025

State technology offices juggled a lot in 2025: modernizing legacy systems, integrating artificial intelligence-powered tools, confronting cybersecurity threats, navigating tight budgets and delivering accessible digital services.

They also grappled with a rapidly evolving policy landscape under the second Trump administration. From cancelled grants and sweeping federal program changes, to cascading political stalemates and disagreements over government’s role in regulating tech, this year proved just the value of agility for top tech officials and state agency leaders across the country.

There were five stories that persisted throughout the year, shaping how nearly every state tech agency adjusted, pivoted and actualized their goals. As state IT leaders balanced innovation with these constraints and aims for compliance, they showed how to institute broader transformation while piloting often unpredictable waters.

A moratorium on state AI laws

If 2024’s biggest state IT story was the boom of generative artificial intelligence, 2025’s was the moratorium that President Donald Trump enacted via executive order earlier this month, preempting state AI laws. Executive and legislative arms of the state governments have spent the past several years crafting guardrails for consumers and use of the tech inside state government, with thousands of bills introduced and hundreds passed so far. In 2025, all of that work was thrown into limbo with the concept of a moratorium.

The idea of a moratorium on state AI laws was first shopped last spring, when a provision was included in a draft of H.R. 1, or the One Big Beautiful Bill — the broad, budget reconciliation legislation loaded with Trump administration priorities that eventually was passed in July. While the moratorium was dropped from the bill’s final text after a resounding 99-1 vote against the measure, whispers on Capitol Hill signaled it had not been defeated just yet, as top Republicans offered suggestions to pass the measure independently, or include it in another large spending bill or authorization package.

State leaders and the groups representing them immediately pushed back. In June, the National Association of State Chief Information Officers, the National League of Cities, the Council of State Governments, the National Association of Counties, the United States Conference of Mayors and the International City/County Management Association authored a joint letter to congressional leaders opposing the measure.

Several experts have predicted that the order will face legal challenges, claiming it oversteps states’ rights. At the end of November, a bipartisan group of 36 state attorneys general sent a letter to Congress also opposing AI preemption. While noting the benefits of AI, the AGs said the risks it poses, such as scams, deepfakes and harmful interactions — especially for vulnerable groups like children and seniors — make state and local legal protections essential.

Proponents of the moratorium say it alleviates the often burdensome cost of compliance on small businesses, and helps to bolster technological innovation. Trump’s executive order, while offering carveouts for laws that govern states’ internal uses of AI, could still impact state laws that extend to local governments, schools and other public entities. Laws interpreted as regulating AI vendors beyond the terms of their contracts with state and local government agencies might also be affected. But the full moratorium’s impact — and its legality — may come into clearer focus in 2026.

BEAD changes

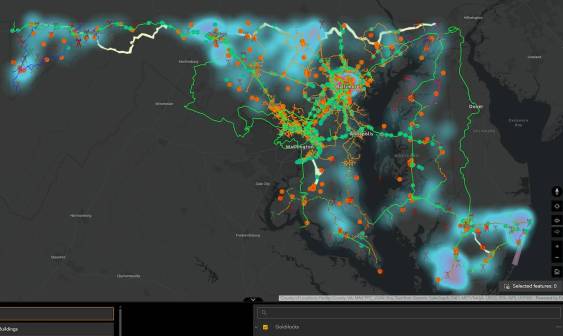

The expansion of high-speed, reliable broadband access nationwide has been seen as an essential part of giving governments, businesses and communities the connectivity needed to deploy and scale AI tools, cloud services and digital applications.

But just a few months after his appointment, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick announced his intentions to “revamp” the $42.45 billion Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, removing what he called “burdensome regulations” imposed by the Joe Biden administration on states and internet service providers. These included the program’s labor, employment and climate reporting requirements.

The updated BEAD program guidance was officially published in June, sending state broadband offices into a scramble to readjust their proposals, and to conduct another round of project bidding referred to as the “Benefit of the Bargain Round,” which instructed states to select the lowest cost bidders for each project. (As of Dec. 19, 37 out of the 56 states and territories have had their BEAD final proposals approved by NTIA.)

They also revoked any prior proposal approvals and wiped away the program’s original rules about “nondeployment” funds. Despite pleas from lawmakers, the new rules for nondeployment funds have yet to be published.

The new rules also dropped the program’s original “fiber first” preference, which opened more pathways for states to spend BEAD funds on technologies like low-Earth orbit satellites and fixed wireless. While this was a move that some states, like Louisiana, were pushing for, the program changes delivered billions to SpaceX’s Starlink, which is owned by billionaire and former “special government employee” Elon Musk.

But those rules are currently under the microscope. In mid-December, the Government Accountability Office found that the National Telecommunications and Information Administration violated the Congressional Review Act when it did not submit its new BEAD rules to Congress prior to issuing them, and that they could therefore be legally ineffective.

Leadership transitions

While states were left to contend with instability stemming from the federal government — as demonstrated by the previous two items on this list — internal changes also created turbulence. A number of state tech offices faced leadership transitions, losing or gaining the chief information officers who set technology priorities.

Eleven states underwent CIO transitions in 2025. Many resulted from retirements or gubernatorial transitions. And some transitions were less transparent than others.

At the top of 2025, states such as North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and Indiana kicked off the New Year in flux. In North Carolina, Teena Piccone stepped up to replace Chief Information Officer Jim Weaver, who’d served as the CIO leading North Carolina’s IT department since March 2021.

In Tennessee, CIO Stephanie Dedmon announced her retirement, triggering a search for a new CIO throughout the first part of the year. In March, Tennessee announced that Kristin Darby, a former health care and finance executive, would be its new CIO. Just north, in Kentucky, CIO Ruth Day announced her resignation, leading to the promotion of longtime Deputy CIO Jim Barnhart in May.

In Indiana, following the departure of CIO Tracy Barnes at the end of 2024, ahead of a new governor taking office, Indiana Gov. Mike Braun in March named Warren Lenard, an auto dealership executive, as the state’s new CIO.

Some leadership transitions were more opaque. Amaya Capellan, the Pennsylvania CIO, and Chief Technology Officer Brian Andrews stepped away from their roles under unspecified circumstances in October. Capellan has said little publicly on the issue, only noting on LinkedIn that “leadership and I agreed that this was the right time for a transition.” Bry Pardoe, who had served as executive director of Pennsylvania’s Commonwealth Office of Digital Experience, or CODE PA, since its formation in April 2023, was named in October to be Capellan’s replacement.

Laura Clark, Michigan’s CIO, quietly resigned after nearly 20 years with the state government this month. Clark shared in a post on LinkedIn on Dec. 30 about her next role at Michigan State University as assistant CIO.

Dwindling federal cyber funding

Just like the uncertainty surrounding BEAD and state AI laws, state tech leaders also faced sweeping declines in federal support for state and local cybersecurity efforts. This year saw substantial changes to both the operations of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, which was created by the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act under Biden.

In February, the Department of Homeland Security discontinued funding for the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center, or EI-ISAC, a program housed at the nonprofit Center for Internet Security that provides training, threat-monitoring services and shares resources with elections officials in state and local government offices across the country.

In March, CIS’s Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center lost funding and its cooperative agreement with federal government, disrupting several of its services, including stakeholder engagement, cyber threat intelligence and cyber incident response. This generated uncertainty for jurisdictions that had been receiving free or heavily subsidized cyber services, and forced the MS-ISAC to begin charging for services when it fully lost federal support later in the year.

New grant rules issued by DHS also prohibited localities from spending SLCGP funds on MS-ISAC services, further restricting how states and localities could use their awards. While the SLCGP continued to remain active with about $91.75 million allocated under the Infrastructure law, this was significantly less than earlier years, and the program is now set to expire.

As cybersecurity support from the federal government dwindled, state and local officials began to prioritize self-reliance instead.

In November, there was legislative movement to reauthorize the SLCGP program, including the House passage of the PILLAR Act, which would extend and stabilize grant funding until 2033. However further action has yet to be taken, and questions remain about future federal support for state and local government’s cybersecurity efforts.

Government shutdown

State agencies also reeled from the impacts of programs temporarily shuttering or defaulting because of the record-breaking federal government shutdown this fall. The shutdown stemmed from a stalemate over extending subsidies from the Affordable Care Act.

The 43-day shutdown disrupted the flow of reimbursement checks to state and local governments, as well as other vessels of federal support that many states normally rely on for major technology and infrastructure projects. This, in many cases, forced governments this fall to delay or rethink spending and planning.

One of the shutdown’s most notable impacts on state and local operations were the lapses in November to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits. The federal government announced it had “insufficient funds” to pay full SNAP benefits, affecting about 42 million Americans, including low-income families, seniors and children.

The lapse forced state agencies to scramble in covering the difference, as they were already grappling with technical, financial and policy adjustments required by H.R. 1. The law reshaped how programs like Medicaid and SNAP would be administered, including expanding work requirements, eliminating nutrition education and increasing state administrative costs.

A report published in October by the Digital Benefits Network and the Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation at Georgetown University found that updating these state eligibility and enrollment platform technologies presents a challenge to implementing the changes required by H.R. 1. Many systems are decades old and costly to modify.

And as these administrative systems were thrown into uncertainty — a direct consequence of the shutdown’s interruption of federal operations — states also contended with the uncertainty of whether they’d receive reimbursement even if they were to cover SNAP benefits in the absence of federal funding.

State agencies managing the Women’s, Infant, and Children’s program also began to brace themselves for potentially sharp increases in demand because of the shutdown’s impact on the SNAP program. But the impact was much more far-reaching: One expert told StateScoop’s Priorities Podcast that the shutdown caused “states and localities to fundamentally rethink their partnership with the federal government,” the effects of which are likely to be felt as we head into 2026.