Machine learning is helping this North Carolina county keep up on property assessments

Math is a part of daily life for property assessors in Wake County, North Carolina, but the agency recently found itself with an equation that had no easy solution. A new requirement dramatically increased assessors’ workload, forcing officials to broaden their search for an answer.

It came not in hiring more people, but in a judicious use of machine learning. Assessors in the county of more than a million residents are now backed by software that provides an objective viewpoint when their own data and expertise falls short.

Until recently, the Wake County Department of Revenue was required to assess the value of the county’s some 400,000 properties once every eight years, William Putney, deputy assessor for the county, told StateScoop. Figuring out how values have changed since the last assessment takes about three years, he said. The process includes a detailed study of the market and then a roughly yearlong window when people are allowed to appeal the new valuations on their homes, which many do.

In 2016, the county — which includes state capital Raleigh and fast-growing town of Cary — opted to do its assessments every four years, which increases the county’s four-year costs from $3.5 million to $6 million and also puts increased strain on staff. Putney said he wouldn’t be surprised if that requirement is further intensified to the point that his team of 16 staff appraisers is doing this job constantly. Even during the eight-year cycle, it was already getting tougher, he said, and Wake County had to hire outside contractors to ease the workload.

These days, though, it makes less sense to hire temporary help for a job that’s no longer temporary, Putney said. So last year, the county began using data analytics software from the Cary-based software firm SAS Institute called Viya that crunches the state’s numbers and produces reports that help assessors make more objective decisions on how to value properties and project for the future.

Viya continues in a long tradition of data analytics products made by SAS — the first version of its software, called simply SAS, was originally developed at North Carolina State University in the 1960s to analyze how different variables affected crop yields before the company was incorporated in 1976. It’s since grown into a common data analytics platform for private businesses and governments alike, and while Viya bears similarity to the company’s core product, and also shares many of its components, it also has enough technical differences to set it apart.

The important thing, Putney says, is that Viya is reducing the frequency of a mistake that has traditionally ended up costing his agency a lot of time.

Eliminating bias

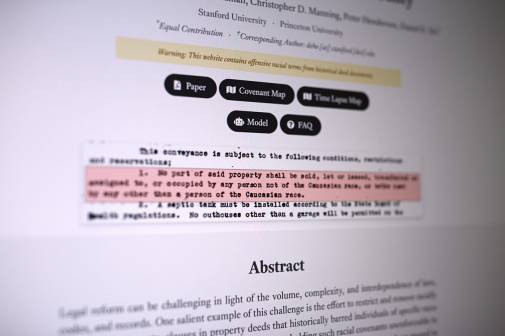

Determining how much a piece of property is worth is essentially a math problem with a lot of variables — assessors consider things like lot size, heated square footage, and how much nearby homes recently sold for. There are many more variables that come to bear, but few are more telling than recent market activity. The problem comes, Putney said, when trying to evaluate how property values have changed in an area where people aren’t doing much buying and selling.

“You really are relying on the appraiser to know where to look for similar neighborhoods,” Putney said.

When there isn’t enough market activity in a neighborhood to give a reasonable baseline to work from, Putney explained that assessors will piece together data from five similar neighborhoods. But determining which neighborhoods are similar is a subjective endeavor and prone to bias. In urban areas, setting the boundaries of neighborhoods is an additional challenge that even longtime residents squabble about.

“The real beauty to me is that SAS is taking a lot of our data, objective data, and they have developed reports for us based on this machine learning,” Putney said. “It’s a nice counterbalance to the staff that we have in our office that’s very knowledgeable but also subject to bias, whereas this data that we’re being provided from SAS — at least to my mind — is purely objective.”

The goal, ultimately, is to limit mistakes related to market activity — and thus limit the amount of time and money the agency spends on handling appeals from taxpayers.

Jonathan Wexler, product manager for SAS’s machine learning business, told StateScoop that the power of the software comes from its ability to bring different kinds of users together on a common project.

“If you’re more of a business user — maybe you’re a domain expert but you’re not familiar with the machine learning methods — they’re presented with more of a visual drag-and-drop experience,” Wexler said. Wexler said.

More technically inclined users can change views and dig into the data, and anyone can see a list of factors and quickly find hidden patterns, he said.

Wake County assessors are calculating property values now that will become active on Jan. 1, 2020. Trying to predict market deflation and inflation is another challenge that SAS helps the county with through something called “time adjustment factor reports.” The county can compare its own projections with the software’s and where there are disparities, look into the contributing factors to see where calculations may have gone wrong.

Limiting appeals

There are perhaps fewer job titles that come with less cachet than “county assessor” — but it’s important work, Putney said, because these evaluations underpin the government’s property tax system.

“The whole system of taxation is built on equity and fairness,” Putney said. “And so if we do not do a good job equitably reflecting market values, then the public loses their trust in the system. And that, as you can imagine, would not be good for anyone.”

Putney says his office receives a mix of legitimate and questionable attempts from homeowners appealing the new values placed on their homes. Some people get creative, like one homeowner who attached a 10-minute video of floodwaters raging through his property — proof of the damage — and another less successful appeal from an audio hardware enthusiast who shared a graph of decibel levels from readings of the freeway that his house backed against. Putney says his office also hears a lot of claims of “deferred maintenance.”

The software doesn’t process appeals or integrate the information shared by homeowners who appeal, but rather it arms the agency with data analysis that it hopes will lead to more accurate valuations, thereby cutting down the number of legitimate appeals it gets. A certain number of people who want to avoid increased property taxes will appeal the new valuations no matter what, but Putney said the state owes it to everyone else to provide the most accurate valuation possible.

Ultimately, Putney says, the fewer appeals his office receives, the more trust it will have preserved in the public.

“Of course, all that’s tied back to cost,” Putney said. “The less time we have to spend on appeals, the less contractors and the less staff we need and so all that goes back to best use of county’s resources.”