Without federal funding, next-generation 911 plods along

Emergency call centers across the country are steadily trading in their analog call-taking equipment for modern devices packed with new features designed to bolster public safety, while call providers swap out copper wiring for fiber-optic cables. These efforts are part of a national push toward next-generation 911, a digital replacement for an aging emergency response system that experts told StateScoop is long overdue.

But the project doesn’t have a consistent funding source, so it’s being cobbled together piecemeal. Several times in recent years, lawmakers have attempted and failed to fund the upgrade — the House’s most recent $10 billion legislation is currently mired in an unrelated political squabble and lacks a Senate companion bill. And even if it passes, it wouldn’t cover all costs — current estimates place a total upgrade at $12-15 billion.

Next-generation 911’s most alluring feature is its ability to handle digital media, like photos and videos from call-takers, which could provide first responders with a richer picture of the dangerous scenes they’re approaching. But the technology’s staunchest advocates told StateScoop they’re more interested in the new system’s improved reliability, speed and accuracy, particularly as the nation’s senescent 911 platform falters.

Brandon Abley, technology director at the National Emergency Number Association, a group that has for years been pushing Congress for a nationwide upgrade, said states and local jurisdictions are making progress on upgrades, but the lack of federal funding threatens to sow stark inequality in the nation’s emergency response capabilities.

“Jurisdictions are not funded equitably in the U.S.,” Abley said. “Each state has its own 911 fee, some states don’t have one at all, some states have something called a 911 fee and that one or two dollars on your phone bill is just spent on something else. The [Federal Communications Commission] gets mad about it, but that’s all they can do. It’s a state issue.”

‘Have and have-nots’

Abley, who’s helped develop the suite of standards defining next-generation 911’s technical architecture, said the major carriers and device makers are “doing all the right things” as the FCC develops rules requiring carriers to deliver calls compatible with a digital 911 system. But the nation’s 5,500 public safety answering points, the industry term for 911 call centers, make their funding decisions independently and upgrades aren’t happening evenly.

Brian Fontes, NENA’s chief executive, warned that inequitable funding and disparate governance could lead to a needlessly unfair future for those calling for help on their worst days. If next-generation 911 delivers on its promise of faster response times by police, firefighters and paramedics, but it’s not available everywhere, then living in the wrong ZIP code could mean an early death for some.

“If we don’t do it as a nation, we’ll be a nation of have and have-nots,” Fontes said.

Abley said more than half of Americans live in a jurisdiction with an active next-generation 911 project at some stage of implementation, but it’s more complicated than that.

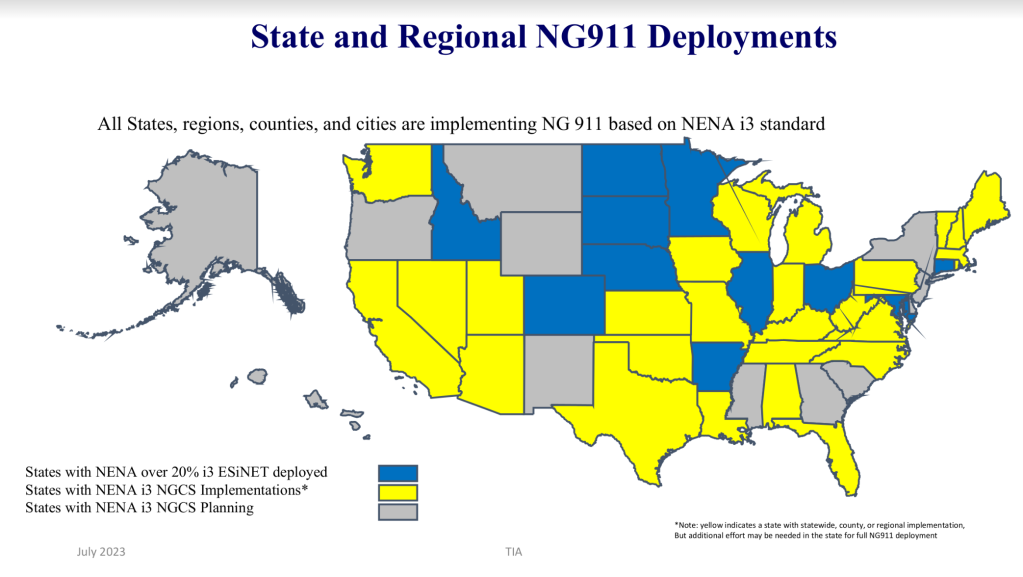

Harriet Rennie-Brown, executive director of the National Association of State 911 Administrators, told StateScoop that more than 40% of states have prepared an emergency services IP network, or ESInet, to serve as the backbone of their next-generation 911 systems. A map hosted on her group’s website shows the patchwork of progress across states, but belies the project’s true complexity.

“It’s not like, oh we flipped the switch and our NG911 is up and running,” she said. “First of all, you have to build that IP-based network. And then you have what’s called the legacy network gateway, where you’re able to run your legacy analog calls into that digital network. And then you have that transitional phase where you’re running everything on IP-based, but not necessarily geo-routing it.”

Other parts of the upgrade include equipping answering points with new equipment and software and providing consumers devices and networks that can handle new 911 features. Rennie-Brown said states also need consistent data platforms for geographic information systems and to switch on next-generation 911 functionality, called “core services,” on their ESInets.

The FCC is currently developing rules in response to a petition from her group that would help clarify which places have upgraded what. She said a “readiness registry” will lend clarity and help inform distribution of funding. And new FCC rules that set project deadlines would help keep everyone on track, she said.

‘It’s time’

But aside from needing funding, Rennie-Brown said, many states still need to get organized. Some have long had statewide 911 administrators, while others, like Nevada, only recently created the role. She said photos and videos are nice, but she’s most interested in the increased reliability that comes with a “self-healing” network. Next-generation 911’s interconnectedness allows network nodes to cover for neighbors during outages, ensuring fewer calls are missed.

“We know it’s time for something modern,” she said. “It’s time to move everybody in the country to next-generation 911.”

Far from being self-healing, today’s 911 systems are dropping a growing number of calls. California’s 438 answering points last October experienced a collective 33,000 minutes of network downtime, a figure that ballooned to nearly 125,000 minutes by December. Budge Currier, assistant director of public safety communications at the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, told StateScoop in March the spike is further proof of the need for an upgrade.

Paul Troxel, 911 branch manager for Cal OES, said at a recent conference in Sacramento that the state’s new next-generation 911 network has far more redundancy than the existing system — with backup systems for backup systems, including a statewide microwave network, called CAPSNET, that Troxel said has never gone offline, even during the devastating 1994 Northridge earthquake.

“Everyone says it’s pictures and videos,” he said. “It’s more than that.”

The technology is here, Troxel said — someone just needs to turn it on. He pointed out that calling 911 in California near a freeway or government building is likely to forward the caller to the wrong law enforcement jurisdiction, and a 911 caller at an airport has a better shot of being found by an Uber driver than an ambulance.