Zoning codes are confusing and controversial, but this startup says it can help

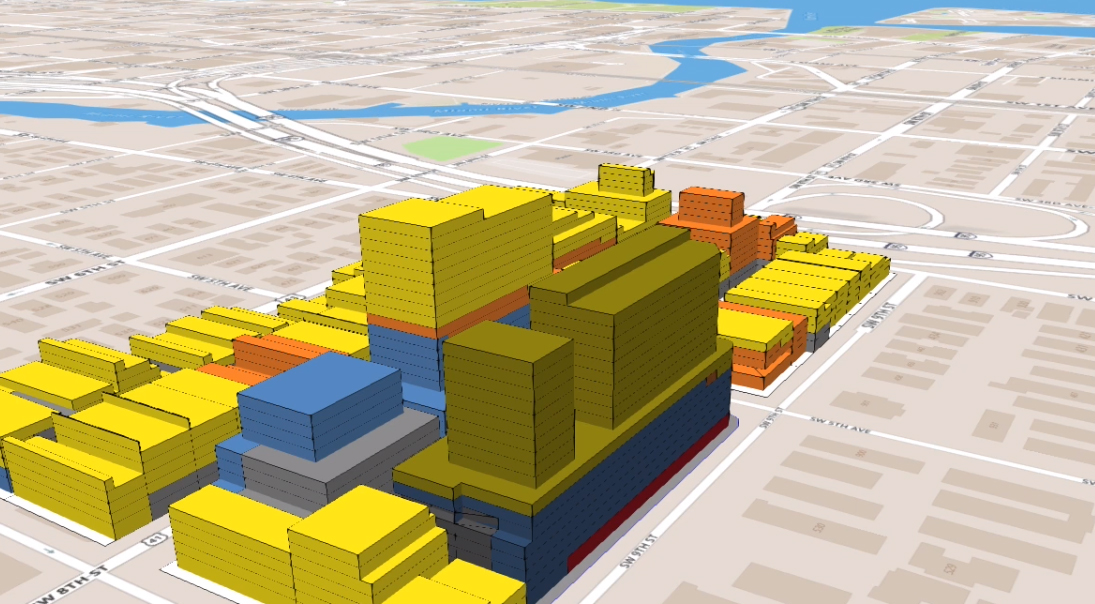

City governments and residents alike typically struggle to understand zoning codes, the rules that dictate where and how things should be built. A new company called Gridics says that by providing builders and city officials with detailed visualizations of how the codes apply to specific sites, it can eliminate confusion and advance local discussions on how best to reform them.

The goal, according to the company’s top executive, is for local governments to regain ownership of discussions that frequently become lengthy, controversial and expensive when there is any talk of changing the existing code, but also to lend transparency to a set of rules that for most members of the public is obfuscated by its bulk. Instead of sorting through hundreds of pages of code to piece together how the applicable rules fit together for a given property, the software, called Zonar, shows how the rules fit together.

The company starts by digitizing a city’s code so that it can be integrated with the software’s computational rules engine. Then, when someone has a question about how a city’s code applies to their building project, the software provides 3D models and detailed reports that show how the code specifically applies to the proposed project and what they can expect going forward.

“The person at the counter [at a city agency] is typically an entry-level person, so you can’t expect them to know every component of the code, but citizens are coming in and they are kind of expecting that,” Doyle said. “Our system allows that front desk person just to type in their address or select their parcel on the map and it just automatically calculates everything — shows setbacks, lot coverage, and gives a point of reference to have a conversation.”

In political settings, too, Doyle said, clear pictures of what’s being discussed are indispensable to furthering a discussion. Last month, Austin Mayor Steve Adler suggested that the city start over on its land use code revision after six years of development and $8 million spent on external consultants, citing a public discussion that had become “divisive and poisoned” and a gigantic code that had become widely misunderstood.

“A picture is worth a million words,” Doyle said. “They say, ‘Just show me.’ And if you can’t show them, it injects doubt.”

In July, Gridics was named as one of six startups that will be given an opportunity to pitch products to the city of Kansas City, Missouri, as part of its Innovation Partnership Program. The city of Cupertino, California, told StateScoop it’s tinkering with the software but hasn’t gotten far enough along yet to render an opinion on it. But Michael Sarasti, Miami-Dade County’s chief innovation officer, said that when he first saw an early version of the software being tested last year, he was “really impressed.”

The rules in Miami’s own form-based zoning code , called Miami 21, can “get pretty intense,” Sarasti said, so having tools that will help people understand them are going to become increasingly important in the years to come.

“Products like Gridics’ start to [make us think,] ‘Maybe [developers] don’t need to come in for everything,'” Sarasti said. “There’s a good percentage of things we’re asking people to come in and discuss that they could probably figure out on their own.”

In Miami, the software is being tested for preliminary plan reviews, also known as “dry runs,” that give builders on larger projects a chance to see what they’re up against before they prepare for a real review. For Miami it’s a low-volume enterprise — Sarasti said the city does maybe two a month, but that the city is evaluating using the software on a wider scale.

Today, developers that have partnered with the city have been given access to the tool via secure remote log-ins. Sarasti said he would eventually like the tool to be made publicly available online as an extension of the city’s open data offerings.

Miami 21 was approved near the tail-end of former Miami Mayor Manny Diaz’s two terms in 2009, and Sarasti said the change was “painful and still probably painful because it’s complicated, but ultimately, it changes the face of the city I think for the better.”

“It’s a challenge because of the complexity,” Sarasti said. “It’s important to have tools that help you manage that, understand that, so you don’t lose the narrative that you’re going to build a great city.”