Philadelphia did its homework before launching municipal ID program

After several years of careful planning, the city of Philadelphia announced Thursday it has joined the ranks of cities that offer municipal ID cards.

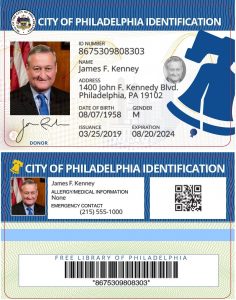

Called PHL City ID, Philadelphia’s new city identification card is modeled after similar cards offered in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York as a way to offer new perks to locals while also increasing access to services for those who may have a difficult time obtaining identification from the state.

Amy Eusebio, the program director for Philadelphia’s municipal ID program, said the city has taken care to avoid some of the pitfalls other cities have stumbled into in recent years. Municipal IDs have generally been received with praise but have also occasionally backfired on those they were designed to assist.

“We did our homework,” she said.

Recently paroled prison inmates, undocumented immigrants or anyone with a Philadelphia address who wants to show their city pride can now obtain a card granting access to municipal buildings and discounts at museums, restaurants and ride-hailing services. The cards are accepted by local law enforcement and the city is now negotiating with local banks and credit unions to accept the IDs.

Recently paroled prison inmates, undocumented immigrants or anyone with a Philadelphia address who wants to show their city pride can now obtain a card granting access to municipal buildings and discounts at museums, restaurants and ride-hailing services. The cards are accepted by local law enforcement and the city is now negotiating with local banks and credit unions to accept the IDs.

One reason for the program’s creation is that many people who don’t have a state ID or driver’s license find themselves in a catch-22 as they attempt to enter municipal buildings or apply for jobs, Eusebio explained.

“One [use] is for someone who might have recently gotten out of prison, maybe their documents are in a family member’s house or were stolen from them,” Eusebio said. “If they no longer have their Social Security card or birth certificate and they want an ID, it kind of becomes a chicken and the egg situation.”

Applicants must still provide proof of identity and residence for a municipal ID, but there’s a broader list of authenticating documents that are accepted to get a card — high school ID cards or face sheets issued by the state Corrections Department are accepted, for example.

Eusebio said the project was conceived by Mayor Jim Kenney when he was still a city council member back in 2015 or earlier, but it took a few years to get off the ground because the city wanted to make sure the program was done right.

“A lot of other cities told us ‘I wish I would have done a slower, more intentional roll out before going live,'” Eusebio said.

As one of municipal ID’s early adopters, New York City launched IDNYC in 2015 primarily as a means to protect undocumented immigrants, but the city subsequently found itself in a legal tussle with federal immigration authorities that sought to obtain the city’s applicant records as a potential arrestee list. In 2017, a Supreme Court judge ruled in favor of the city’s right to destroy the records rather than hand them over, but the incident highlighted the thin line so-called sanctuary cities were riding as they gathered information from many who were at risk of deportation.

Eusebio said Philadelphia won’t keep any copies of documents and only maintains the minimum required information to verify that a given municipal ID is authentic — the cardholder’s name, birth date, card issue and expiration dates, and an ID number.

But some immigration advocates have begun to question whether the cards are a potential liability for immigrants after a couple who last year displayed their IDNYC cards at a military base in upstate New York where their son was stationed were ultimately arrested. This February, several immigration advocacy groups said they would stop supporting New York’s municipal ID program altogether if the city went forward with its plans to add financial smart-chips to the cards, which critics say could put cardholder privacy at risk.

Philadelphia’s ID cards don’t have smart-chips and the city is now working with the Pennsylvania Bankers Association and the Pennsylvania Credit Union Association, which Eusebio said are both supportive of the program. Individual financial institutions in the city will next decide whether they want to participate in accepting the cards.

Another key consideration that delayed Philadelphia’s program was how to craft contract language that would ensure the city owned the data and could secure it. Eusebio said the city considered several different technology models and ultimately settled on a hybrid model with Omicron Technologies in which the company consults the city, procures and owns technology, but the city administers the cards and owns the data, which is kept on a secure cloud-based server.

“We take the protection of our resident data very seriously,” Eusebio said. “And we feel like [the data we’re storing] is minimal enough that there shouldn’t be great risk of exposure to our residents.”

According to the city, the cards meet “the federal government’s Level 1 identification standards for physical security features” but the cards do not meet Real ID standards, so the cards can’t be used for entrance into federal buildings or airports.

Because of the methodical approach used to build the program, Eusebio said she feels confident in its future success and is now looking forward to the many great perks the cards offer. Applicants can opt to include on their cards a library bar code, self-identify a gender, include military status, or label medical conditions like epilepsy or diabetes.

“People really appreciate that,” she said. “We’re trying to reach a broad range of people and get everyone to sign up and show their Philly pride.”

Cards cost $5 for children 13 and up and $10 for adults up to age 64. Seniors are free and the city is not charging for the first 1,000 cards.