How cities are using data to fight climate inequity

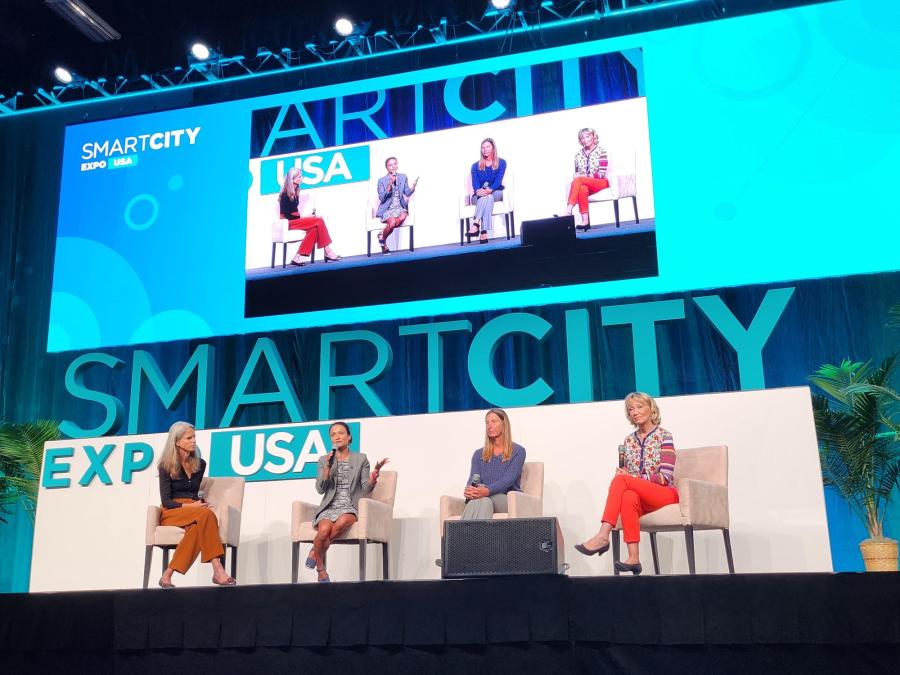

Speakers at the Smart City Expo USA conference at the Miami Beach Convention Center are no strangers to extreme heat.

The city has experienced record-breaking heat in recent weeks, and high temperatures impact the city’s residents in different ways, Jane Gilbert, Miami-Dade County’s chief heat officer, said during a session Wednesday. Gilbert was the nation’s first-ever chief heat officer, a role that is becoming increasingly common as cities and counties struggle to adapt to scorching weather and understand how climate impacts housing, health, education, work, and ultimately, the quality of life of their residents.

A big part of Gilbert’s role is coordinating conversations between county departments to help people better manage their environments, whether that is in their home, place of work, or somewhere in-between, she said. Bus stops, she said, are risky, and residents waiting for transport in extreme heat, with no shelter or tree canopy, can end up in the emergency room.

“We can’t AC ourselves out of this problem,” Gilbert said. “We don’t want to create solutions that are going to exacerbate the root cause of the problem.”

Planting more trees is one solution, but community engagement, localized data collection and pushing for wider policy change are important in achieving wider change, said Gilbert. Miami-Dade is now, for example, pushing for statewide reform to ensure all new construction is built with cool roofs, which reflect more light than conventional roofs.

“Not every community has a heat officer, but whatever your role, I urge you to think about who is experiencing this change the hardest, and how you can take that into account,” Gilbert said.

Julia Kumari Drapkin, CEO of the nonprofit ISeeChange, and Tiffany Troxler, director of the Sea Level Solutions Center at Florida International University, both said it’s important for cities and other local governments to consider that extreme weather risks may be underreported in low-income areas and over-estimated in higher income areas.

Flooding may be underreported in areas where residents speak English as a second language, or don’t engage with city services such as 311, Drapkin said. She also noted that large studies on the efficiency of windows or other home fixtures at the state or federal level may not be conducted in areas where people don’t own their own homes.

In one New Orleans heat study, Drapkin and her colleagues found that building inefficiencies made it nearly impossible, not to mention expensive, to cool entire homes.

“We need to be targeted and tactical in our solutions,” she said.

If a whole home can’t be cooled, then it makes sense to at least ensure bedrooms are a comfortable temperature so that residents can sleep well, she said.

Extreme weather can expose inequities, and in a city like Miami, where there is wide socioeconomic variation, people can experience extreme heat or flooding very differently, said Troxler. By understanding which ZIP codes, and even which blocks, are most at risk, cities can facilitate more targeted support. Collecting that level of localized information, and finding solutions, will require collaboration not just with citizens, but economists, planners, engineers and communicators, she said.

“We need to start thinking differently about how we design our environments,” Troxler said.