We need to finally complete a national spatial data infrastructure

The U.S. is battered by numerous $1 billion natural disasters each year, but yet we still lack ready access to accurate, up-to-date geospatial data and decision support tools that would help the nation respond to and prepare for these emergencies.

A National Spatial Data Infrastructure, or NSDI, as first imagined in the 1990s, would provide such authoritative data and tools. And while strides have been made toward creating this infrastructure, particularly with the 2018 passage of the Geospatial Data Act, we have yet to make the critical commitment to fully develop it. Communities still lack the geospatial data, tools and capabilities to better understand their risks and vulnerabilities and to identify the most effective disaster mitigation efforts.

We need a more encompassing national method for overall coordination of policies, data, technologies, education and resources necessary to support geospatial data sharing and application.

The importance of building the NSDI is not well understood. While a vast quantity of the location data collected by government, private industry, higher education and nonprofits ends up in the public domain, there are still large gaps in data availability and tons of duplicative work resulting from a lack of coordination.

Critically important geospatial data is often insufficient or unavailable in many areas due in part to a lack of national coordination. This lack of a shared data infrastructure puts lives and livelihoods at risk.

Since a landmark 1994 executive order signed by then-President Bill Clinton, the creation of the NSDI has been focused on the creation and sharing of data, but we need an increased emphasis on the application of shared data for improved decision support.

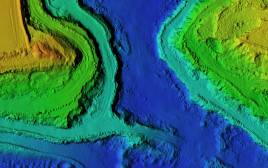

The 3D Elevation Program led by the U.S. Geological Survey, for example, unites federal, state, local and tribal governments — and the private sector — in advancing a detailed, nationwide elevation model that’s become of critical importance in addressing issues such as flooding and landslides. However, there are many other instances in which government, private companies and other groups undertake independent efforts to create and maintain what is fundamentally the same information, such as the duplicative collection of address data.

The Census Bureau collects address data, but it’s restricted by statute from sharing it. States are currently cooperating to create a separate National Address Database for broader government and public use. But if data managed by the Census Bureau were anonymized and shared, it could help avoid the duplication of an effort that’s crucial to the success of a national spatial data infrastructure.

Duplicative geospatial data collection needlessly costs the United States hundreds of millions of dollars.

Other geospatial data efforts remain scattered, leading to critical gaps in data coverage. Data is often misaligned or old and can’t aid in vital problems. It often takes longer than necessary to acquire and align data, which costs time, money and lives. Data providers are everywhere but they’re often not working together cohesively. Without complete nationwide coverage of critically important geospatial data themes — transportation, hydrography, addresses and parcels, for example — we may never be able to act in an informed, coordinated and decisive manner.

A shared, next-generation NSDI requires a national approach in which all interested parties coordinate as a unified, connected whole, much as each member of an orchestra fills a specialized function while staying in tune and in rhythm with the rest of the band.

There is some good news: Geospatial data professionals have identified a set of data commonly needed across a multitude of use cases. These “framework” data can be assigned to various entities for maintenance based on factors like data type and jurisdictional authority. Local authorities are in charge of detailed private land ownership records, for example.

Meanwhile, integrated spatial data infrastructures are manifesting in regional systems, such as the Southern California Association of Governments and in Arkansas, Indiana, Minnesota, North Carolina, Oregon and the District of Columbia. And new approaches for public-private partnerships forged by the Federal Geographic Data Committee, or FGDC, show promise.

Unfortunately, the FGDC’s budget has been decimated over the years, severely hampering its GDA-mandated mission to unite stakeholders in the governance and coordination of the NSDI. Furthermore, non-federal stakeholders are in many cases producers and maintainers of geospatial data aggregated to the national level by the federal government and private sector, yet they are limited to an advisory role in the FGDC governance process.

New collaborative SDI governance approaches have potential to build upon and fundamentally improve the way we work together across the public and private sectors to address the challenges we face. The time is now to establish a more inclusive, national governance and coordination approach that further advances the NSDI through expanded stakeholder representation, equitable engagement and greater sharing of ideas, solutions and resources.

The conversation is already underway. If you are interested in being part of this dialogue, contact us at the National States Geographic Information Council.