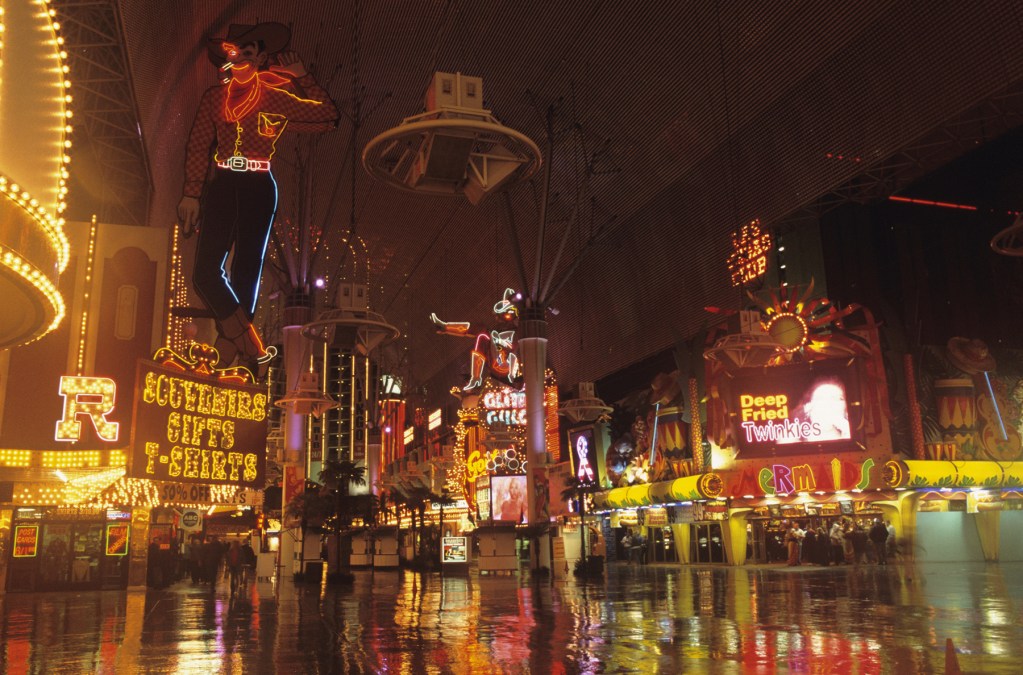

Las Vegas tests new sensors to make one-way streets safer

To strike a balance between privacy and safety for pedestrians, cyclists and drivers in its busy downtown, Las Vegas is testing new infrared cameras and lidar-based sensors that track movement without identifying individuals behind the wheel or walking and pedaling down the street.

The city began a year-long pilot project in late 2018 with the Nevada state government, Dell and NTT, a Japanese telecommunications company, to use internet-connected audio and video sensors to manage vehicular, pedestrian and bicycle traffic. While the city has used technology to reduce collisions before, this attempt is geared toward making Downtown Las Vegas’ one-way streets safer, said Michael Sherwood, Las Vegas‘s director of innovation and technology.

“If we knew how many accidents that were almost occurring as well as ones that did, would we change our methodology on installing traffic-calming measures or pedestrian measures to help ensure the proper signage is there?” Sherwood said.

Simply recording and counting traffic collisions is one way to collect data, but Sherwood said NTT’s optical sensors, which are being placed in intersections or on light poles around the city, can detect near misses as well using infrared vision or lidar, a laser-based surveying tool that measures distance.

“What we’ve found out is while we didn’t have a lot of accidents on a [one-way] street, we did have a lot of people going the wrong way,” he said.

The sensors, which also collect audio information to help discern where cars are on the road, use Dell software to compute the audio-visual data on the edge, or within the sensor itself. Metadata is then sent back to a central repository for the city to analyze. Las Vegas will own all of the data collected during the pilot period.

“Instead of sending all the data back to a core, trying to analyze it and send something back, even though that might take milliseconds, it really is not helpful if you’re trying to change a light from green to red based on a condition,” Sherwood said.

Infrared and lidar, which is commonly used on semi-autonomous vehicles to detect their immediate environment, don’t necessarily detect details — just the shapes of objects. The city doesn’t need to know if a car is white or blue, or what the driver looks like, to know if it went the wrong way down a one-way street, Sherwood said.

“We just need to know that a vehicle went the wrong way,” he said.