‘Community of practice’ key for GIS success, says Wisconsin official

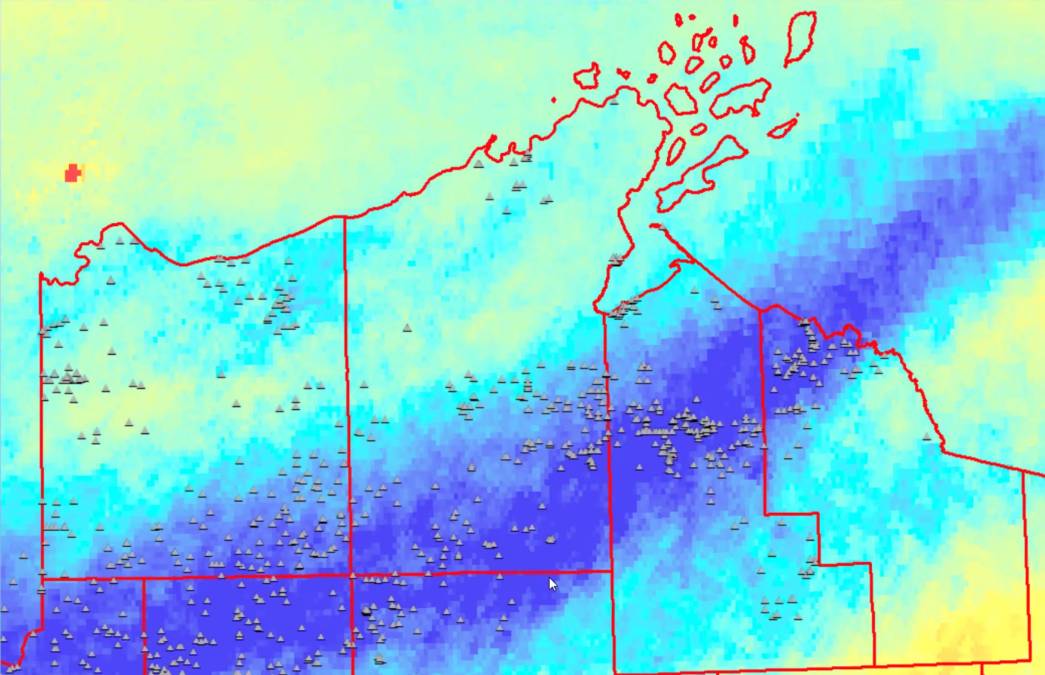

Three little-publicized storms that did more than $100 million in damage to the northern reaches of Wisconsin over the past decade have occupied much of Jim Giglierano’s time in recent years. As Wisconsin’s geographic information officer, Giglierano and his office’s partners have been mapping the four counties bordering Lake Superior in an attempt to understand the damage and how to plan for similar weather in the future.

In a presentation to the National States Geographic Information Council membership on Wednesday, Giglierano pointed to several of the technologies that have enabled the state’s Department of Administration to make headway in addressing the storm damage, but said that it’s partnerships with local government agencies that possess unique expertise on the region that’ve been most helpful.

“We especially want to cut across organizational structures,” Giglierano said. “Wisconsin government is a very siloed sort of state of affairs. People in the same agency don’t know that their mapping counterpart exists across the cubicle. So we’re trying to bomb that, and especially try to get into the local folks, as well.”

The storms, which struck in the summers of 2012, 2016 and 2018, didn’t receive much attention because few people live in far northern Wisconsin, but the damage to local roads, pipes and water culverts was substantial, and repairs have been integral to the mission of the state government and local water conservation departments and watershed associations.

Giglierano said that developing a “community of practice” that includes those organizations has been helpful in resolving technical challenges, such as resolving differences in how various mappers plot “cutlines” — map features that indicate where there’s water — and gaining a more accurate accounting of the terrain.

“There’s a lot of expertise and a lot of knowledge out there and sometimes it leaks through and sometimes it doesn’t,” Giglierano said.

In one attempt to harness the state’s distributed expertise, Giglierano’s office developed a cloud-based geographic information systems tool so organizations with fewer resources would have access to the kind of technology and computing power available to the state government and its university partners, he said. But officials discovered other challenges, especially a lack of GIS expertise among many smaller organizations, like local road departments.

Giglierano said the state was helped out by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which lent one of its coastal management fellows to conduct a statistical analysis of land characteristics associated with damaged water culverts. The preliminary analysis, which Giglierano warned anyone against “hanging their hat on,” showed that slope, soil type, size of culvert, land cover and stream length all showed some correlation with storm damage. The NOAA fellow took another job before the work was finished, but continuing the work could be useful, he said.

Giglierano’s review of the storm damage is based on more than 270,000 map points and 23 inventories of culverts and water features, collected in data sets his office requested from statewide agencies, counties and local government divisions.

The database isn’t intended to replace that already used by the state’s transportation department, he said, but it might find wider use, including by the federal government. Giglierano said his database can be used for flood modeling, fish passage modeling, asset management, invasive species control or to inform the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s disaster relief and hazard mitigation grants.

Giglierano asked the NSGIC audience for help in solving some of his agency’s challenges, and said his next 18 months of work will focus on providing local road departments with tools they can use to support this work, despite their lack of GIS expertise.