Local governments use GIS to find and fix inaccessible sidewalks, curb ramps

To prioritize the repair of inaccessible public infrastructure like cracked sidewalks and degrading curb ramps, local governments in the Midwest are turning to data and geographic information systems.

Two neighboring governments — Lawrence, Kansas and Douglas County, Nebraska, which houses Omaha, the state’s most populous city — are using mapping software from Esri, paired with other technologies, such as artificial intelligence tools and lidar, to ensure their curb ramps and sidewalks are compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The 1990 law prohibits discrimination against those with disabilities by guaranteeing that public accommodations and commercial and government facilities are accessible to all.

Under the ADA, the two governments are responsible for maintaining hundreds of miles of sidewalks and thousands of curb ramps. By not fixing them, they face costly liability issues and ADA violations. But to manually identify infrastructure in need of repair, Douglas County officials estimated, the effort would take about 1,000 man hours.

Lawrence previously approached improvements to its sidewalks and curb ramps as “smaller spot repairs,” said Evan Korynta, the city’s ADA compliance administrator. But in 2021, he said, the city began developing a long-term plan for achieving complete ADA compliance.

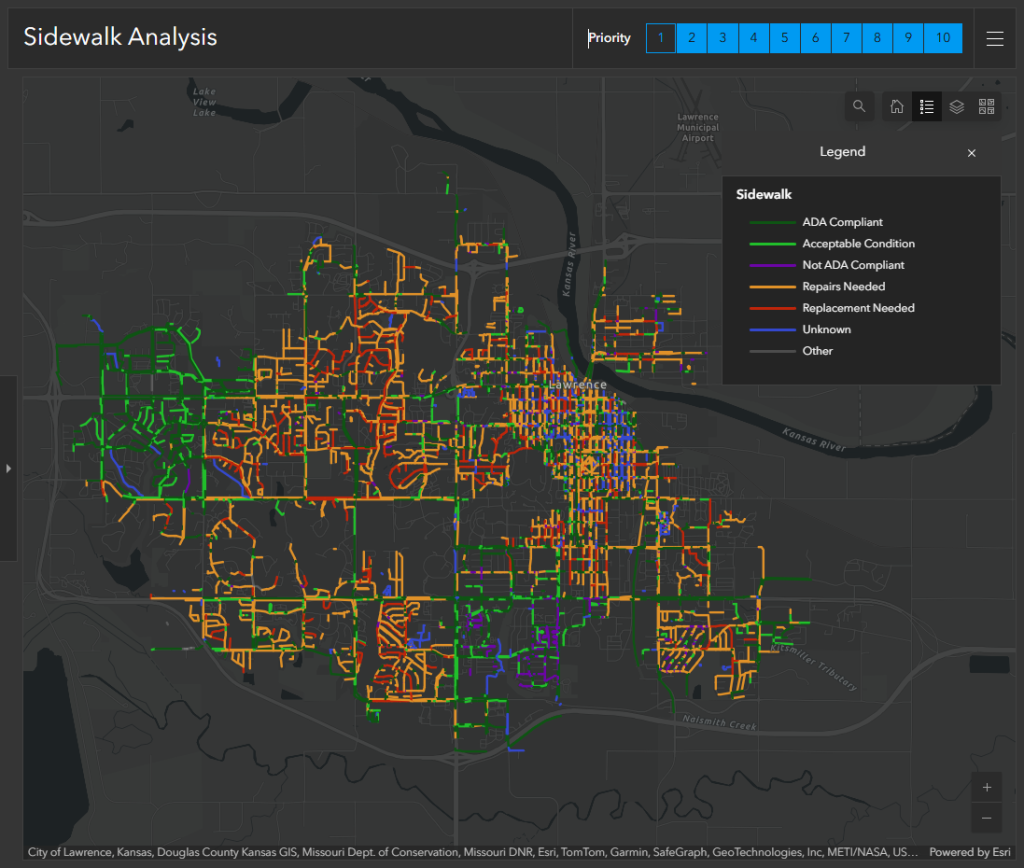

Using a slow moving vehicle equipped with lidar, a mapping technology that uses laser light to measure distances and render 3D models of objects and landscapes, Lawrence officials said they were able to efficiently survey more than 420 miles of sidewalk and 6,500 curb ramps — but the results weren’t great.

“We actually were able to see that through years of deferred maintenance and not really staying on top of this, we were left with about 70% of our curb ramps and sidewalks needing help,” Korynta said.

City officials also pulled in demographic data — such as disability prevalence, median household age, pedestrian demand and limited transportation access — and layered the datasets in Esri’s ArcGIS, a tool widely used by government agencies. Officials said it helped them determine where the high-priority areas were.

With the data, city officials drafted a more in-depth ADA transition plan, which the law requires, that shows how the city will remove barriers to accessibility in transportation systems and public facilities. This plan, the officials said, was presented to local policymakers and helped the city to secure the funding necessary to make the improvements.

The layered datasets also allowed the public to become more engaged in the process, said Jessica Mortinger, Lawrence’s transportation planning manager. She said that was important because, in Kansas, some property owners are required to maintain their own sidewalks.

“Before we had our formal ADA transition plan, where we were mostly doing our just sidewalk improvement of hazards, now we’re doing full reconstruction in places where we the hazards are too extreme to just do repairs. And that includes block-end to block-end in reconstruction,” Mortinger said.

The mapping tools have helped the city develop a transparent, long-term plan formulated with community input for bringing sidewalks and curb ramps into compliance.

The project is expected to cost more than $100 million over the next 20-25 years, city officials said.

“It’s been a really beneficial tool, not only for our inspection staff to quickly get through inspected areas, but just to really have a public-facing record of what we’re telling folks that we’re seeing and what the work’s going to entail for us to make these corridors completely ADA compliant,” Korynta said.

About 200 miles north of Lawrence, officials in Douglas County and Omaha, Nebraska, are also using GIS to help formulate their plans to tackle ADA compliance. But to determine the scope of the project, Steve Cacioppo, senior GIS analyst at Douglas County, trained a deep learning AI model to help plot curb ramps throughout the county.

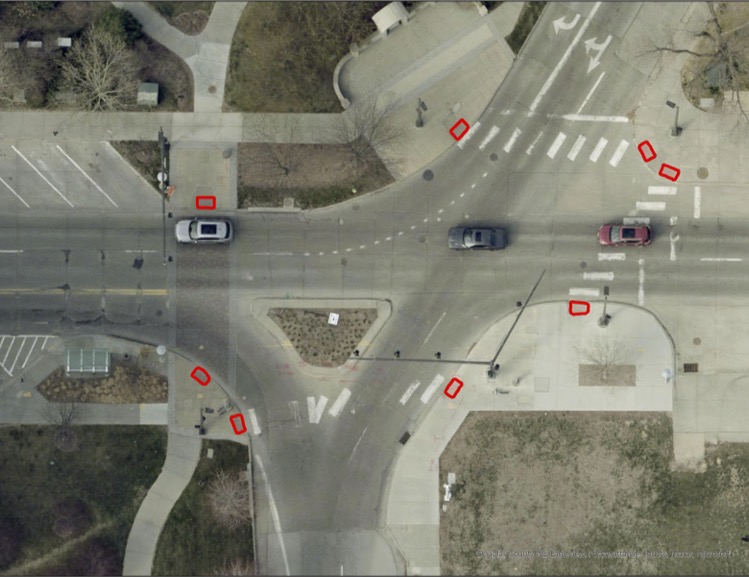

When the effort kicked off in 2022, Cacioppo said, the city had an incomplete curb ramp inventory. Using high-resolution aerial photography, Esri’s GeoAI, a suite of deep learning AI models, and 700 sample images of curb ramps, he trained an AI model to automatically index the locations of curb ramps.

After several rounds of trial and error, Cacioppo said, the deep learning model mapped out more than 34,000 curb ramps across the county, and that data informed its latest ADA transition plan. He said the deep learning model did the work in 12 days, compared to six months it would have taken a human inspector.

While the AI couldn’t tell city officials whether each curb ramp was ADA compliant, the location data allowed the GIS team to update their inventory. And that inventory also allowed them to build an app for reporting compliance of constructed and repaired ramps, said Todd Spark, the maintenance superintendent at Omaha’s public works department.

Spark said the app is in the beta testing phase, but for each ramp, the app will list out all the criteria that needs to be met for each portion of the ramp: the ramp, the landing, the transition and the slope. Additionally, the tech has saved the city least $30,000 for the manual inspection of each curb ramp just in Omaha, Spark said.

“They figured for somebody to go through manually and do all that, it would probably take them about 1,000 hours to go through the entire county,” Cacioppo said. “That’s half of a full time employee — and that’s if that person could focus for eight hours and actually do a good job and keep that speed. But we’re all human, and we know that that job would be horrible, and it would likely take longer than six months to do that. So, that was a big return on investment right there, just having this model run.”