How cities and states are preparing for the first digital census

Fearing an undercount as the census goes digital in 2020, many states and cities are investing in technology.

Advocates of census tech initiatives — which range from digital literacy programs to mapping software — say the projects have the potential to hold the census accountable amid unprecedented challenges. They’ve cropped up in states across the country, but California, by far, is leading the charge.

The state has launched a campaign of staggering proportions for the 2020 count, pledging $187 million to census initiatives at all levels of government — six times more than any other state. And at the heart of California’s strategy, state officials told StateScoop, is a $1.7 million data portal.

The mapping and demographic data in the portal will direct the efforts of canvassers as they knock on doors across the state to spread awareness of the census count, in what Paul Mitchell, the vice president of Political Data, Inc., a firm that is developing software for California’s census campaign, called “the largest field organizing campaign we’ve ever seen.”

“We’re expecting it to be larger than a combination of all the competitive races we had out here in California’s last election cycle,” he told StateScoop. The enormous, data-powered effort is a sign, he said, of what California stands to lose in the census, and why tech might be the solution.

Hard to count

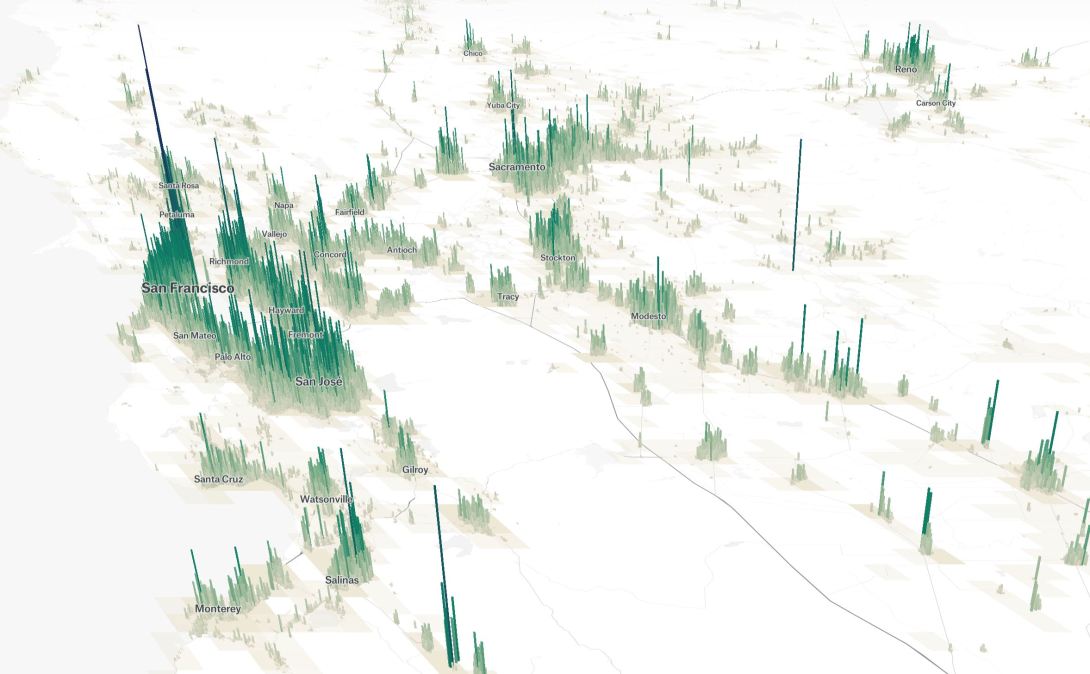

Worries about the census in California have been running high among officials and advocacy groups. They base much of their concern for the 2020 count on a map maintained by the City University of New York that identifies the most difficult populations in the country for the census to pin down. In California, like much of the Southwest, large areas blaze yellow and red on the “hard to count” map, signaling historically low census response rates.

California’s census data tool, nicknamed SwORD, or the Statewide Outreach and Rapid Deployment portal, stores this kind of mapping data — layering onto the map other factors that predict when neighborhoods are at risk for census undercounting, like whether another language is spoken in place of English, or when neighborhoods have high numbers of renters.

Those types of hard-to-count demographic groups, who are more likely to either miss the census entirely or be unfamiliar with the count, make up almost three quarters of California’s population, according to some analyses. Reports by the Urban Institute and others show that the census tends to disproportionately undercount low-income communities and people of color. And for the state, a census undercount could mean a loss of a seat in Congress or federal funding slashed by tens of millions of dollars, California has projected.

That risk could be further heightened in 2020, as the census moves online for the first time. Though the census bureau will ship paper forms to anyone who does not initially complete the form online, some say the bureau isn’t diverting enough resources to get a good count in areas with poor internet service.

“I think [the digital divide] is more extensive than perhaps folks have realized. Groups on the ground see it a lot. I don’t know if the bureau recognizes, potentially, how big that gap actually is,” said Maria Filippelli, a census fellow at New America who is working on census tech initiatives. When state government steps in, she said, “it really helps amplify what groups are doing.”

Acting when it matters

SwORD stores data on broadband’s availability and speed and, project reports say, will make it available to more than 500 census partners in California, such as community organizations or tribal governments. When Census Day hits on April 1, 2020, the database will keep tabs on the results, allowing outreach organizations to pivot immediately to areas with poor early-response numbers.

“It’s a data-driven approach,” said Diana Crofts-Pelayo, California’s census spokesperson. That, she said, is the “most important piece” of the state’s census plan.

Political Data is designing a mobile app to pair with the database, which would funnel data back from canvassers about the households they visit. It’s pricey software that’s usually used in well-financed election campaigns, but when the company’s contract with the state is finalized in the fall, Mitchell said, outreach organizations will get the app free of charge. California plans to spend $750,000 to acquire the platform, according to budget documents.

As California charges ahead with the plan, Mitchell said he sees other states falling behind.

“I don’t necessarily see other states taking this kind of really aggressive route,” Mitchell said. “And I’m fearful that, post-2021, there are going to be a lot of people that have this light-bulb moment of, ‘Oh, we really should have done something when it mattered.’ Because it’s not like you’re going to be able to go back afterwards and fix it.”

Funding gaps

City and state IT officials said they see California as a shining, moneyed example of what tech can do for census strategy. But most don’t have that kind of cash.

Twenty-nine states have directed no funding whatsoever to census efforts, according to National Conference of State Legislatures records — leaving cities and community groups to piece together digital strategies themselves.

That’s been a challenge for the city of Philadelphia, said Stephanie Reid, the executive director of Philly Counts 2020, the city’s census committee. Pennsylvania’s state census committee in May recommended the state divert $12.8 million for the census, but the state’s budget, which it unveiled in June, included no census funding.

$39 billion in Pennsylvania’s federal funding is tied to census data, according to the GW Institute of Public Policy. It’s used for programs like Medicaid, education grants, and public housing, which rely on population figures. Wrong estimates can lead to reduced resources for these aid programs. But the story goes beyond federal funding, Reid said.

“Census data drives a lot of business and funding decisions. If Wawa is saying, “Where are we going to put our next Wawa [store] in Philadelphia,” it’s going to look at census data. They’re going to figure out what communities are growing,” she said. “That’s going to be a big part of their decision about where to expand.”

In an effort to keep within its plateauing budget, the census bureau has also cancelled planned testing and cut regional offices as 2020 approaches. In 2010, Reid said, Philadelphia received $545,000 from the federal bureau for community-based census efforts. That money was eliminated in 2020.

“There hasn’t been a census like this,” she said. “To have the challenges we have and then these gaps in funding… it’s a different world.”

Digital concerns

One of Reid’s main concerns for the census, she said, was digital access in Philadelphia, which has been ranked as one of the country’s “worst-connected cities” by the National Digital Inclusion Alliance. In 2017, it found nearly one in four of the city’s roughly 600,000 households had no internet access. For answers, Reid said she looked to the city’s Office of Innovation and Technology.

Reid’s conversations with the city’s IT officials led her to focus the city’s census initiatives on digital literacy. Philadelphia’s innovation seed fund, the Digital Literacy Alliance, is now giving out $200,000 in grants for the census this year, thanks to those talks. The Alliance is still reviewing project proposals — considering, Reid said, any initiative that links the census and digital access.

Other, similar initiatives are cropping up around the country. Detroit has launched an extensive digital campaign for the census, using data tactics like California’s to map out their outreach. San Jose piloted a text-message-based mapping tool for the census. The state of Maryland is partnering with public libraries to provide internet access when census forms go out. State officials there say they have developed, like California, their own “hard to count” map.

For Mitchell, this new, data-rich strategy for the census raises new questions, both in California and around the country. For the first time, he said, technology has advanced to the point where states and cities have the means to get counts of their own.

“What if, in the city of Santa Ana, [California], the census comes out and says, ‘There’s X number of [residents].’ But we now know, because of all the knocking and phoning and work on the ground, that there’s Y number of residents,” he said. “What is the state going to do at that point? Is it going to challenge the census?”