Mayors pass resolution against paying ransomware ransoms

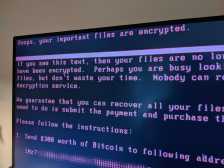

Baltimore Mayor Jack Young announced on Wednesday that the U.S. Conference of Mayors has passed a resolution calling on cities not to pay ransom to hackers who have taken over government computer systems through cyberattacks.

Young, whose city of Baltimore had its computer systems disabled by the ‘RobbinHood’ strain of ransomware in May, sponsored the resolution at the conference’s annual meeting in Hawaii last week.

“Paying ransoms only gives incentive for more people to engage in this type of illegal behavior,” Young said in a statement. “I am proud to unify with the U.S. Conference of Mayors to stand up against these types of attacks and show people that they will not take control of our cities.”

There have been more than 170 recorded ransomware attacks against state and local government bodies since the malware first cropped up in 2013. The new resolution matches the recommendation of federal authorities, such as the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security, which advise local agencies not to pay, citing both an undesirable precedent and the possibility that payment may not even lead to a restoration of services and data.

The cost of Baltimore’s ransomware incident, which city officials said last month was approaching 90 percent remediated, is estimated to be more than $18 million — $10 million to repair the city’s computer systems and $8 million in lost revenue from disabled services. Though Baltimore’s ransomers asked for the comparatively small sum of 13 bitcoin, then valued at $75,000, Young has stood by the decision not to cede to the demands of hackers.

John Zanni, CEO of Acronis SCS, a cybersecurity company based in Scottsdale, Arizona, told StateScoop that while he supports Young’s resolution, he believes it will be fruitless.

“I agree with the mayor that you should never pay a ransomware ransom because it encourages them to attack other cities,” Zanni said. “But ultimately it will have zero impact. Ransomware attackers have now gotten a taste for attacking state and local government. They’ve found honeypots of opportunity and they’re not going to stop.”

Of the dozens of state agencies and local governments that have become infected by ransomware viruses, many of them originating from hackers based in North Korea, Russia and Eastern Europe, most of those who disclose the attacks do not pay their ransomers. But there are also rumors of many more ransomware incidents in which the cities do pay and keep quiet for fear of embarrassment or censure from others in government or the technology industry.

Zanni said he doesn’t think cities unifying around refusing to pay will deter hackers, pointing to his own experience as the manager of his family’s French restaurant in Thousand Oaks, California, many years ago. He recalled an incident in which a thief broke in to the restaurant’s back office and stole cash that hadn’t been locked up.

“I learned my lesson. The next time they broke in, a few months later, they did not find any cash, so they set the office on fire,” he said. “Ransomware and hackers have a similar profile. If they can’t get ransom, they’re just going to do it to disrupt the government.”

Zanni said the ideal solution is to prevent hackers from intruding in the first place by buying security tools like those offered by his company and many others. They cost much less, he said, than $18 million.