To challenge FCC’s bad broadband maps, groups demand a regular process

At a House subcomittee hearing on Wednesday, industry stakeholders, broadband advocacy representatives and legislators acknowledged shortcomings in the Federal Communications Commission’s current broadband mapping strategy and built consensus for a consistent and formal process to challenge the commission’s data.

The hearing, held by the House subcommittee on energy and commerce, was held to examine five bills surrounding the FCC’s data-collection and mapping process, which has been scrutinized in recent months by Congress and state employees eager to capitalize on a $20 billion rural digital opportunity fund and more than $600 million in USDA funding for rural regions without broadband.

The bills address different aspects of the mapping process. One would punish ISPs that submit inaccurate data, another would standardize submitted data. Others seek to establish a data verification system and a “location fabric” that would geo-tag every business or home in the U.S. eligible for broadband coverage. Another, the Broadband Deployment Accuracy and Technological Availability Act, or DATA Act, would establish a standing challenge process to ensure the FCC’s coverage data is accurate.

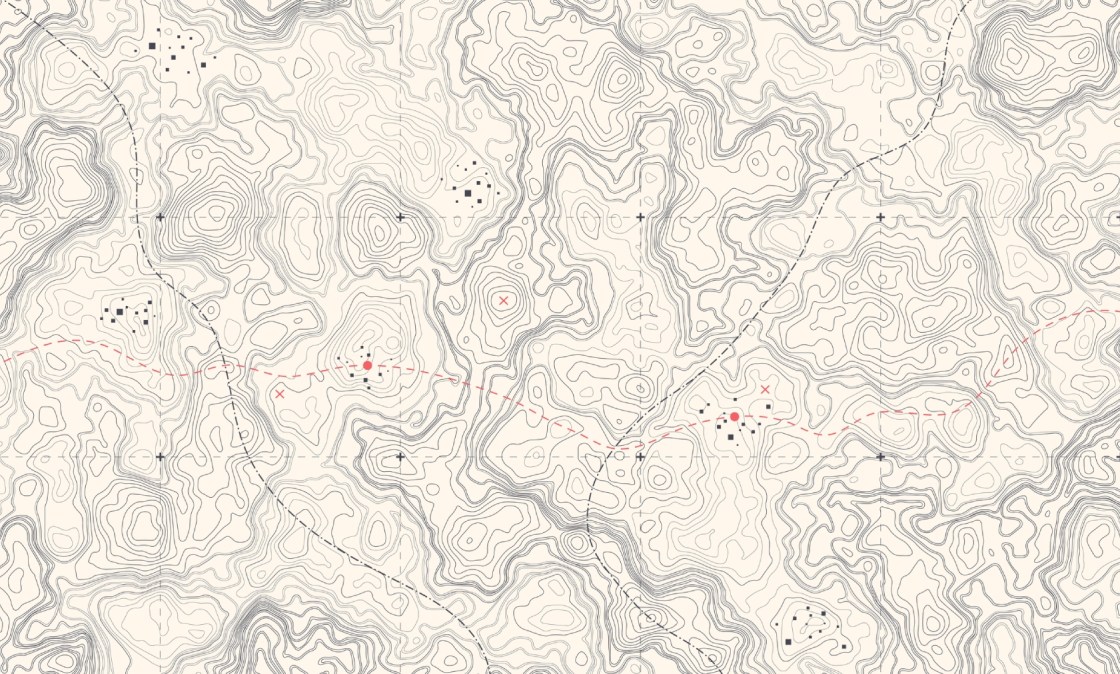

Together, the bills would essentially codify several of the proposals put forth by FCC Chairman Ajit Pai in August, which is collect and develop broadband coverage maps using more granular maps, rather than by census block. Right now, ISPs are only required to provide service in a small area of a census block to count as providing service to the whole block. The block-by-block process was criticized by FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel back in May as an easy method for ISPs to overstate their coverage, especially after Barrier Free, a wireless carrier serving roughly 3 million people in the Northeast, skewed the FCC’s nationwide broadband data by claiming to serve the entirety of New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and five other states.

Though these bills and the FCC’s own efforts to improve the mapping are a positive step forward, argued Shirley Bloomfield, a witness at the hearing and the chief executive officer of NTCA, also known as The Rural Broadband Association, establishing a challenge process that occurs at regular intervals is the most important thing Congress can do to ensure that rural broadband funding goes where it is needed the most.

“I would not move forward without a challenge process,” Bloomfield said. “Whether you go shapefiles, fabric, whatever sequence you’re looking at, it’s still self-reported data [by ISPs],” Bloomfield said. “At the end of the day, the challenge process is going to be really important because it’s your sanity check. It’s the one chance you have to say what’s really happening.”

It’s in the best interests of ISPs to overrepresent their coverage data so that they don’t have to spend money to provide service in sparsely-populated areas, and the FCC’s mapping strategy enables them, according to state employees in Vermont, West Virginia and North Carolina who have or are planning to challenge the coverage maps.

The proposal for a challenge process was also supported by James Assey, a vice president at the NCTA, also known as the The Internet & Television Association.

“Before awarding scarce broadband deployment subsidies based on the map, there should be a means of challenging a provider’s submission of deployment data, an opportunity for the provider to respond to the challenge, and a forum for resolution by the FCC if the parties do not reach agreement,” Assey wrote in his testimony.

Dana Floberg, a policy manager at media and internet advocacy group Free Press, said in her testimony that a successful challenge process would also ensure that provider coverage maps remain publicly available so that researchers — and the general public — will have the opportunity to contest a carrier that’s falsely claiming to provide coverage to their home or office.

“One of the biggest mistakes the FCC made [during the last challenge process] was to not let the American public participate in the challenge process. This legislation gets that right,” said Grant Spellmeyer, vice president of Federal Affairs & Public Policy at U.S. Cellular.

The last challenge process the FCC conducted was maligned by those who participated. Two telecommunications employees within Vermont state government, Clay Purvis and Corey Chase, challenged the FCC’s maps in late 2018 in order to receive a portion of $4.5 billion in rural broadband funding, and called the process “archaic.” Meanwhile, members of West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin’s office, who were unable to acquire new equipment to collect data for its challenge, had to use staff members’ personal devices.

Some at the hearing emphasized the importance of keeping the process public. If the data were to be kept private, Floberg said, it would render a challenge process dysfunctional.

“It would absolutely throw a wrench in the works of having any sort of functional challenge process to get a sense of whether or not the maps and data reported from carriers is accurate,” Floberg said.