AI solved ‘nearly impossible’ task of finding racial covenants in county’s real property deeds

A group of Stanford and Princeton University researchers on Thursday published a paper outlining the near-perfect performance of a large language model they say could help county governments in California and beyond save millions of dollars and countless hours of work as they strive to comply with mandates to redact racist artifacts from real property deeds.

The work, which the researchers conducted in collaboration with the Clerk-Recorder’s Office in Santa Clara County, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area, was inspired by California’s AB 1466, a 2021 law that requires all of the state’s 58 counties to redact from recorded deeds instances of discriminatory language, including racial covenants, widely used clauses that once prohibited non-White people from living in certain neighborhoods.

Although the Supreme Court in 1948 rendered racial covenants unenforceable, the task of redacting them from tens of millions of property records could be costly and tie up local governments’ staffs for years to come. Los Angeles County recently signed a seven-year contract with the Wisconsin technology firm Extract Systems to manage a racial covenant redaction project that may cost as much as $8.6 million.

But according to the paper published Thursday, researchers armed with an open artificial intelligence model managed to sift through Santa Clara County’s 84 million pages of property records — some of which date back to the 1850s — in just a few days. Researchers also expressed confidence that their finely tuned model achieves a false positive rate very close to zero.

The paper reveals that’s an astronomical improvement over a manual review.

“In late 2022, Santa Clara piloted a manual review process with two staff members manually reviewing 89,000 pages of deeds, finding roughly 400 racial covenants,” the paper reads. “At an average of a minute per page, performing a manual review of the entire collection of 84 million pages of records would require approximately 1.4 million staff-hours, amounting to nearly 160 years of continuous work for a single individual.”

California law still requires the county clerk’s office to manually validate each racial covenant the model found before recording the redactions, but the researchers estimated the model saved the local government more than 86,500 hours of work and crushed the project’s cost down to just a few hundred dollars to cover computing costs, a miniscule fraction of what a vendor would likely have charged.

Since ChatGPT’s public release in November 2022, state and local government IT officials have been keen to realize such savings of time and cost. It was just before that milestone that Daniel Ho, a Stanford professor who directs the university’s Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab, also known as the RegLab, suggested to the Santa Clara County clerk they embark on a new project as part of their ongoing partnership.

Ho, a professor who holds appointments at the university’s law, political science and computer science colleges, told StateScoop that the complex project was simplified by the existing partnership between his lab and the county government. For instance, the partnership enabled the researchers to create a data-sharing agreement to circumvent a law requiring the clerk’s office to charge a fee for access to each record.

And the results, he said, have been “remarkable.”

“We knew at the time that the improvements we’ve seen in language models of being contextually aware would likely have pretty significant gains over something like a keyword-based search,” Ho said. “But what was really surprising to us was how material that was in this particular application, particularly in driving down the number of false positives.”

‘Really compelling performance’

Traditional natural language processing techniques, such as keyword searches and the use of regular expressions, a kind of pattern matching algorithm commonly used by computer scientists, are highly effective, but far more brittle than what the latest large language models offer. According to the new paper, keyword detectors tested by researchers had false positive rates of nearly 30%, and they also easily missed instances of racial covenants.

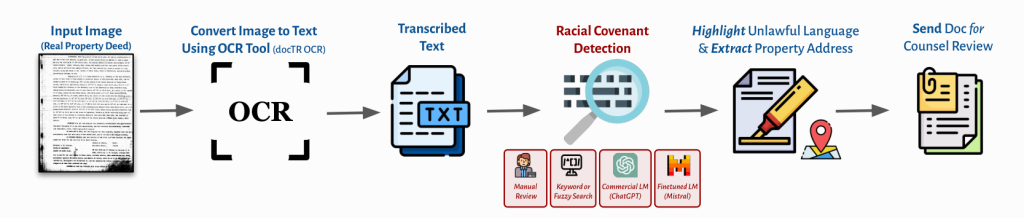

Keyword matching, a technique similar to the types of searches people do inside their web browsers and word processors every day, break down when searching documents that were created by scanning physical records, as was the case in Santa Clara. Beside the fact that words like “white” or “black” are often unrelated to race, matches are missed when optical character recognition, or OCR, software mistranslates letters from their original sources. Some 6 million deeds recorded in Santa Clara before 1980 had been handwritten or preserved on microfiche sheets.

Through the use of regular expressions, researchers created a “fuzzy” matching system that dropped false positive rates of keyword searches down to 2.2%, but Ho said that with the large volumes of documents counties manage, even this quantity of false positives would incur large additional costs during the review process, and so this approach was abandoned.

Researchers also tried “off the shelf” generative AI products, like OpenAI’s GPT3.5 and GPT-4 Turbo models, but found similarly lackluster performance, likely because their training data contained few property deeds.

The technology that was used to parse Santa Clara’s deeds was a finely tuned large language model from the French firm Mistral. Beyond its accuracy, the model also impressed researchers in its ability to derive important context from disparate county documents. During the years when racial covenants were most frequently used — between 1920 and 1950 — developers often drafted deeds for plots of land that contained many homes, referencing locations with phrases like “Map [that] was recorded …June 6, 1896, in Book ‘I’ of Maps at page 25.”

“Remarkably, by extracting these textual clues and cross-referencing them against multiple administrative datasets from the County’s Surveyor’s Office, we show that it is possible to recover the location of individual properties to the tract level (several blocks) for most properties,” the report reads.

Assistant County Clerk-Recorder Louis Chiaramonte admitted in a press release he’d originally thought the mapping task “nearly impossible.”

A side-by-side comparison outlined in the paper estimates a manual review in Santa Clara County would have cost $1.4 million and taken nearly a decade. GPT3.5 or GPT-4 Turbo could do the job in less than four days, costing $13,634 or $47,944, respectively.

But their Mistral model took six days, was far more accurate, and cost just $258.

“What an open model really allows you to do is to really fine tune it to this specific task so that you get really compelling performance for the identification of racial covenants,” Ho said. “A lot of that investment [in proprietary technologies] may not be something you need for these specific use cases.”

‘A striking thing to find’

Ho said the model, along with a web interface tool for building training data, will be shared online to be freely adopted by government agencies, whether it’s clerks in one of California’s 57 other counties or one of the dozen other states — including Minnesota, Texas and Washington — that have passed laws requiring redaction of racial covenants from property records. While California is directing county clerks to make the changes, some states have tasked homeowners with the job.

“One of the big questions has been do we put the onus on homeowners or should we have a more comprehensive effort,” Ho said. “And the challenge with more comprehensive efforts seems to be what L.A. County experienced, which is this could be a really difficult exercise and require huge amounts of time and staff to do. What this project really shows is that you can do that in a completely different way to do much more efficiently.”

To create a tool that was agnostic with respect to document formatting and that would withstand wording from different regions, the researchers also trained their model using about 10,000 property deeds from seven counties from outside California, including Denton County, Texas, and Lawrence County, Pennsylvania.

The tool generates a bounding box for each page where a match is found, making it easy for human reviewers to spot the unpleasant details. California’s law requires that the documents are redacted in a way that preserves the racist language for reference by government officials or historians, but that blots it out on copies reviewed by homeowners or real estate agents.

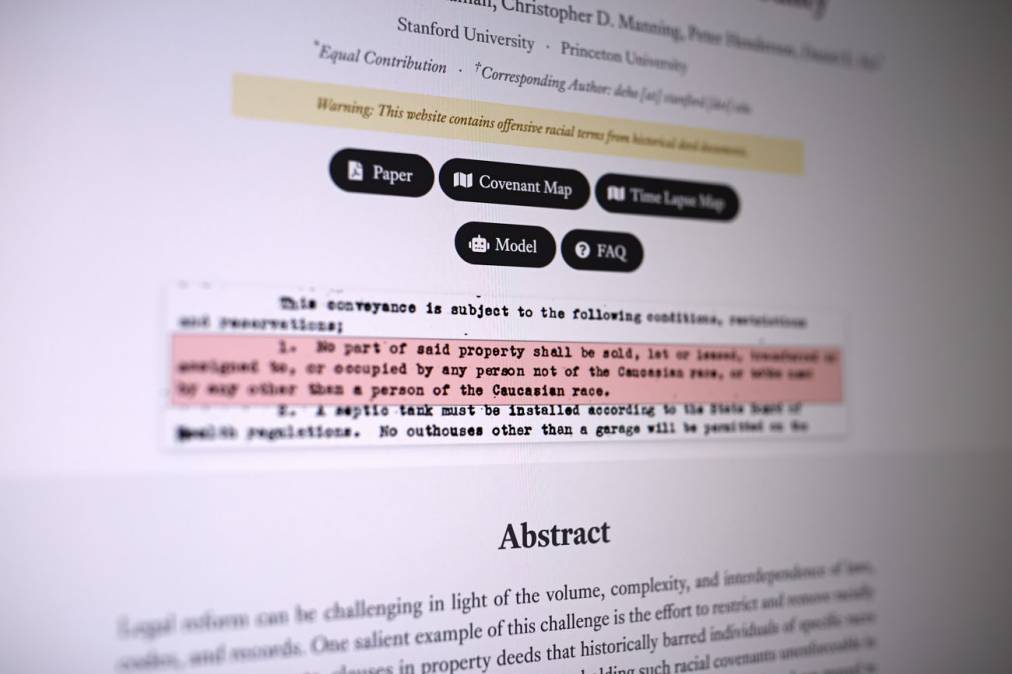

Sandwiched between zoning regulations and a rule concerning outbuildings not being legal residences, one racial covenant from a property deed referenced in the paper reads: “No persons not of the Caucasian Race shall be allowed to occupy, except as servants of residents, said real property or any part thereof.”

Ho, who said he’d learned about racial covenants “in an abstract way” in law school, said he discovered one in his own property document upon buying a house in Palo Alto, California, in 2022.

“I was really quite shocked to see that it stated that the property shall not be used or occupied by any person of African, Japanese, Chinese or Mongolian descent, except for in the capacity as a servant to a white person,” Ho said.

The paper notes that racial covenants were most commonly used to exclude African Americans, but other groups were also frequently excluded — including Asians, Latinos, Jews and Southern and Eastern Europeans — “to maintain racially homogenous, white-majority neighborhoods by barring minority groups from settling in specific areas, and they were actively supported by real estate boards, developers, homeowner associations, and governmental institutions.”

Beyond serving as a neat solution to an expansive technical challenge, researchers explain in the paper that the project can also help to more accurately define the history of racial exclusion in California’s housing market. The report notes that 10 developers were responsible for about one third of the county’s racial covenants, using them to bolster marketing campaigns showcasing exclusive neighborhoods.

Ho estimated that model may also be useful if adapted to find more-rare discriminatory language, such as clauses related to income or family status.

He said his team has continued to analyze the data uncovered by the model, and in recent days they’ve found that racial covenants may be even more common than originally thought.

“Our best estimate right now is that about one of every four properties in Santa Clara County was covered by a racial covenant in 1950,” he said. “It was a striking thing to find.”