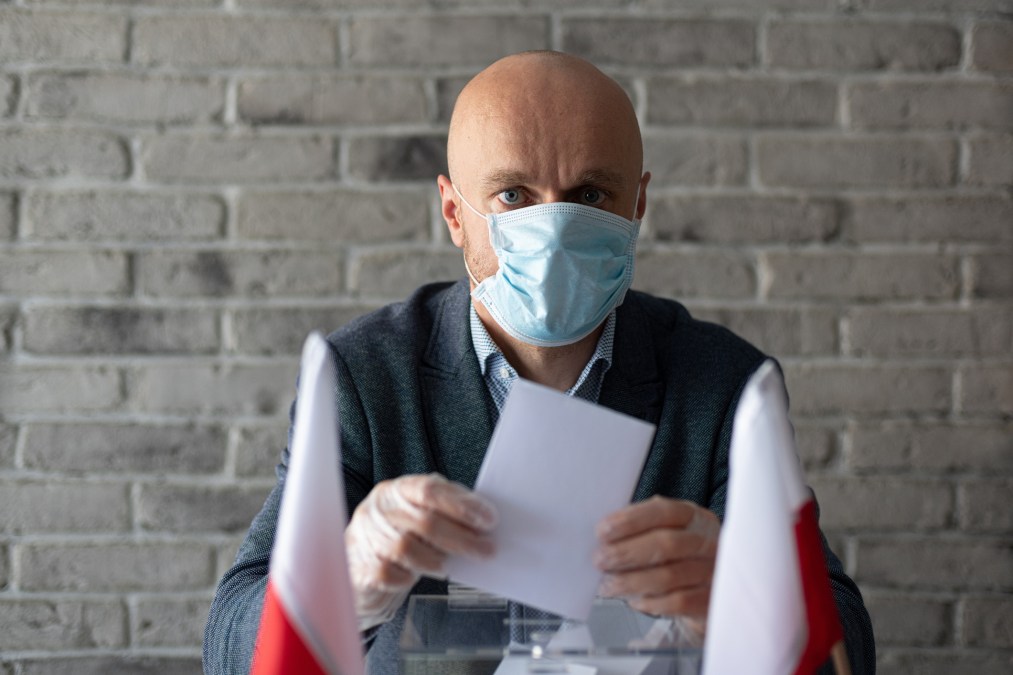

‘Biggest threat to election security is the coronavirus,’ security expert warns

Although the rate of new infections appears to have slowed down in recent weeks, the COVID-19 pandemic remains the greatest challenge to ensuring that the 2020 presidential election runs accurately and securely, election security experts said Monday.

Speaking on a webcast hosted by two members of the House Homeland Security Committee, Wendy Weiser of New York University’s Brennan Center for Law and Justice said election officials still need much more funding and support to make all the preparations for an election that will likely have to be conducted largely via mail, especially in states that have historically low rates of postal ballots.

“By far the biggest threat to our election is the coronavirus,” Weiser said. “We are going to see substantial changes to how we run elections this year.”

A potential preview of November is playing out Tuesday, with seven states and the District of Columbia holding their primary elections, including several that were delayed from March and April as the pandemic spread and kept voters cooped up under stay-at-home orders. In almost all those jurisdictions, election officials — Republican and Democratic — made efforts to expand their use of mail-in ballots.

Rep. Lauren Underwood, D-Ill., the vice chair of the Homeland cybersecurity subcommittee and who is also a nurse, said she wanted to avoid more situations like Wisconsin’s April 7 primary, in which the Republican-controlled state legislature and state supreme court’s refusal to extend the absentee deadline forced many voters to venture out to a limited number of public polling sites.

“I was horrified by the choice Wisconsin voters were forced to make between risking their lives or giving up their right to vote,” she said. “Over the events of the last week, it’s been painfully clear all voices are not always heard. Our patriotic duty is to make sure every voice is heard and every vote is counted.”

But Weiser reminded Underwood and her colleague, Rep. Jim Langevin, D-R.I., that states still need much more money to carry out a largely by-mail election this fall. Weiser recalled an April report the Brennan Center released along with the University of Pittsburgh Institute for Cyber Law, Policy, and Security, Alliance for Securing Democracy and the R Street Institute, finding that the $400 million in election assistance funds Congress included in a March pandemic relief package would cover just a fraction of the costs of switching to predominately mail-in balloting in five states.

Weiser also said that in addition to scaling up printing and postage costs, a massive expansion of voting by mail also concerns many of the vulnerabilities that were exposed in the 2016 election, particularly around states’ voter registration databases, which were prime targets for the Russian military hackers who attempted to disrupt U.S. voting systems.

“The risks that were revealed in 2016 have not gone away,” she said. “Attacks on voter registration databases could have an even more devastating effect this year given how crucial these systems are to absentee voting.”

In total, the Brennan Center and its fellow think tanks estimated states would need $4 billion to scale up their vote-by-mail options. Langevin said the supplemental pandemic relief package the House passed last month includes $3.6 billion in additional election assistance grants, but the Republican-led Senate and President Donald Trump, who votes by mail in Florida, have refused to consider the bill.

Still, expanded vote-by-mail can’t be the only salve for ensuring people vote during a pandemic, said Leigh Chapman, the director of the voting program at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Chapman pointed to images of Texas’ March 3 primary in which predominately black voters at a polling place in Houston faced six-hour lines to cast their ballots.

“Voting by mail is a great option and it should be easy and accessible,” she said. “Voters must also have a clear range of options. Focusing exclusively on vote-by-mail could disenfranchise voters of color, Native Americans, voters with disabilities and the homeless.”

Chapman said states should also get funding to make sure polling places are outfitted for social distancing and other public-health requirement, extend early voting and enabling online voter registration, which 11 states, including Texas, still lack.

One voting method the panel dismissed, however, was online ballot submission, which three states — Delaware, New Jersey and West Virginia — have tested in limited capacities. Langevin said that a paper published on the subject by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency “advised against internet voting because of its high risk, but fell short of opposing directly.”

Weiser gave a more blunt assessment: “As tempting as using online systems for voting may be at this time — and we are looking for every way to increase remote access to voting — it is the Brennan Center’s position it is simply not secure. It’s an open invitation to hackers who are trying to interfere in our election.”