Colorado’s new biometric privacy law may strain small businesses, says lawyer

Colorado legislators in May passed a law making the state one of just a handful to regulate the privacy of biometric data. One former Federal Trade Commission lawyer told StateScoop the broad regulations introduce complications to Colorado privacy law — including by burdening small businesses — that could trickle into privacy laws in other states.

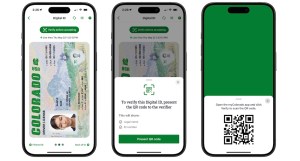

Colorado’s biometric law amends the state’s 2023 privacy act to create new requirements for collecting and processing biometric data for businesses. The law also requires businesses to provide notices of collection, and to create retention schedules and mandatory deletion guidelines for any biometric data collected.

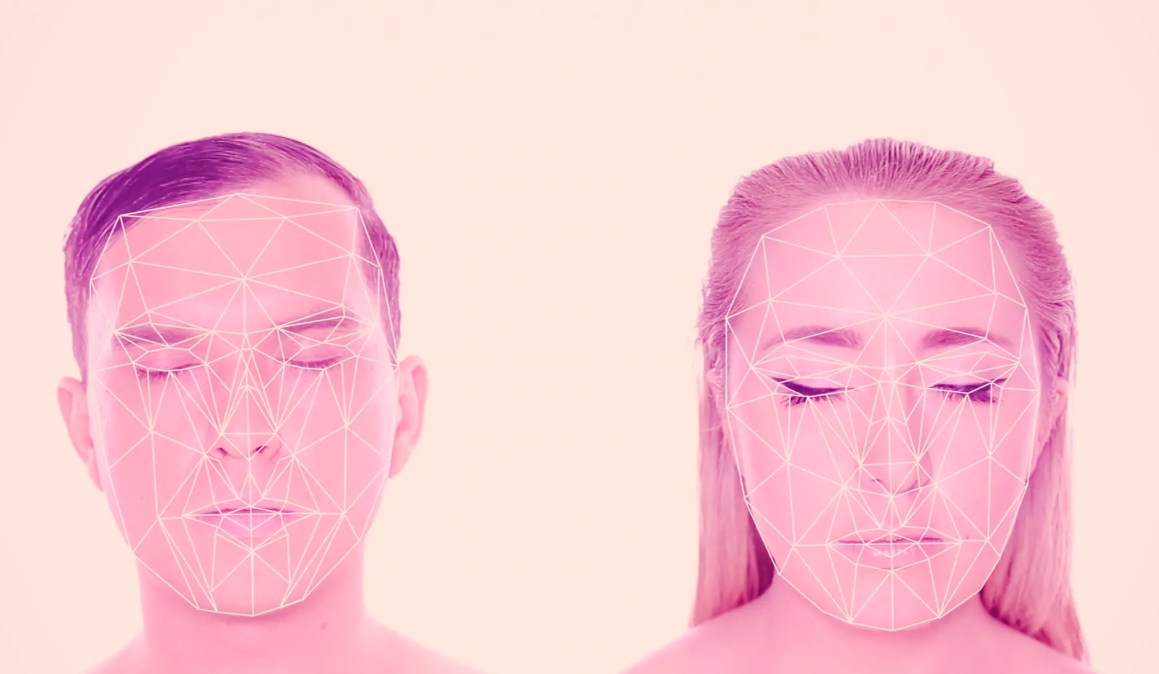

Colorado defines biometric data as information generated by people’s physical or behavioral characteristics for identification purposes, including facial scans, fingerprints, voiceprints and retina scans. It does not include data from photographs or audio recordings.

Maneesha Mithal, a partner at the law firm Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, told StateScoop that the broad application could “run counter” to some of the law’s intended purposes.

Tthe amendments have broader applicability than the Colorado Privacy Act, which only applies to large companies, those that collect information from at least 100,000 state residents. The amendments cover businesses that control or process any amount of biometric information, and they include employee data. But, Mithal said, the amendments left it unclear whether smaller businesses covered by the biometric amendments must also comply with the statewide privacy act.

By joining the handful of other states with biometric laws on the books — a group that includes Illinois and Washington — Colorado continues to posture itself as a state leading on tech and data regulations. In May, Colorado’s legislature also passed a bill designed to mitigate AI-powered discrimination, a move that Mithal said made Colorado the first state to pass “comprehensive” AI legislation. In another first, Colorado in April passed a law offering privacy protections for neural data, information related to brain or spinal activity.

The Colorado Attorney General’s office last month proposed draft amendments to the Colorado Privacy Act, seeking to provide clarity on some of the obligations businesses face under the biometric regulations, and opened the amendments to public comment.

The proposed amendments would require smaller businesses that collect biometric data to comply with the state privacy law’s mandates, but only with respect to their biometric data. The amendments also explain in more detail how businesses must notify consumers and employees about the collection and use of biometric data.

Mithal, who co-chairs the privacy and cybersecurity practice of her firm’s Washington office, said she expects the public comments to feature concerns from small businesses that may not have the resources to comply with the new regulations by the July 1 deadline. She also anticipated businesses will voice concerns about the amendments’ inclusion of employee data and their application to businesses of all sizes.

‘Hard for companies to comply’

Despite applying to businesses of all sizes, Colorado’s biometric amendments feature similarities to the 2008 Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act, or BIPA, which some privacy experts have deemed the gold standard of biometric data laws. But unlike BIPA, Colorado’s law does not feature a private right of action that would allow people to bring legal action against companies found violating the law.

Other states have privacy laws with private rights of action, like Washington with its My Health My Data Act, which while specifically targeting health care data, also applies to biometric data.

In the absence of a federal law, the country’s patchwork of state privacy laws has proven especially challenging for businesses, while Congress has tried and failed twice to set national data privacy obligations. Mithal said this variety in state laws is part of why Colorado’s broader biometric regulations could influence similar requirements in other states, where lawmakers hope to achieve more consistency across state lines.

“Every state law that gets passed has an influence, because states that are considering legislation look to models, and so I think that’s why you see a lot of similar provisions in the different state laws, … but then they’re also looking for innovation, too,” Mithal said. “So, every state is kind of changing the rules of the game a little bit, and I think it makes it really hard for companies to comply. I think that’s why a lot of companies support a single federal standard.”

Mithal said the Colorado amendments could also impair technology innovation, particularly for facial recognition technology, which is controversial in part because it’s been shown to produce false matches. She said that in the legislative findings of Colorado’s latest bill, lawmakers note positive uses of facial recognition, which relies on biometric data. These included using facial recognition to catch shoplifters, and prevent fraud or other illegal activity.

However, the broad reach of the law could stifle any chance for businesses to explore using technologies that rely on biometric data.

“If you look at the findings, they say the obligations under the bill don’t restrict a business’s ability to protect against illegal activity. But in practice, if you look at how broadly applicable the bill is, that may run counter to those goals, because companies that are using biometric information for fraud prevention or to detect illegal activity would be sweeped in under the bill,” Mithal said. “I think that there’s some positive use cases for biometric information that will be made more expensive and more costly because of the requirements to comply.”