State websites don’t meet upcoming DOJ accessibility requirements

A report published this month by a cohort of web enthusiasts shows that no U.S. state website is completely compliant with accessibility standards set by the Department of Justice, like closed captions and compatibility with screen readers.

The findings were published in the Web Almanac, an annual “state of the web” report compiled by web industry professionals who participate in a community web development tracking project called the HTTP Archive. This year’s edition contains 21 chapters covering a range of web best practices, including page content, user experience, content publishing and distribution. The accessibility chapter details the extent to which governments — from countries down to the U.S. states — follow accessibility rules.

An audit of state websites shows none achieved 100% compliance with accessibility best practices, many of which will soon become mandatory after the U.S. Department of Justice last April issued new rules for web accessibility of government websites. The rules added a new component to the Title II regulations of the Americans with Disabilities Act outlining the technical requirements of compliance with the ADA on the web.

Mike Gifford, open standards and practices lead at the software firm CivicActions, authored the government website accessibility section of this year’s report. He said his work was an attempt to provide “a leaderboard of states” for accessibility of state websites.

Gifford said he used Google Lighthouse, a tool used to scan websites on measures including accessibility, performance and search engine optimization.

“We haven’t been able to compare this information before, probably because there hasn’t been an easy way for governments to be able to to crawl all of their domains and be able to have this information,” Gifford said. “Often, governments don’t even know how many domains they have. They don’t keep track of this information very consistently.”

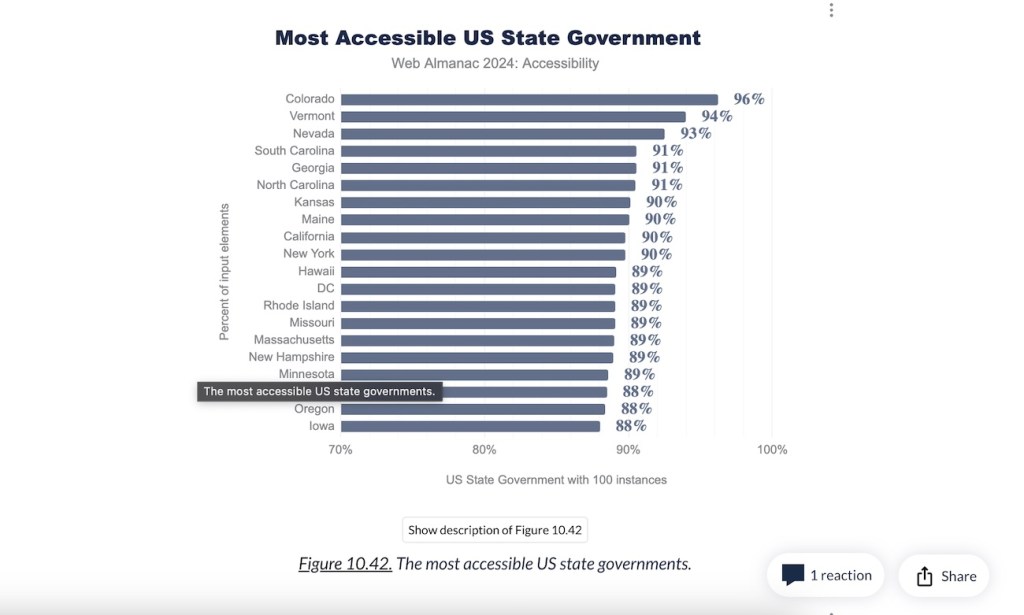

The Web Almanac contains scores for each state, averages of the web practices practices measured. Colorado tops the list, with a score of 96%, followed by Vermont, Nevada, South Carolina and Georgia, all of which scored at least 90%. New York, California, Missouri, Maine and Rhode Island also scored highly.

Gifford said the findings provide a “high level view” of state web accessibility, but that the averages are based on just two webpages from each state website: the homepage and a secondary page. Gifford said if they’re not meeting basic requirements on their home pages, then it’s likely they’re not meeting the rest of the requirements on the whole of their websites.

He said the scores only reflect about one third of the web standards that will be mandated for states as part of the DOJ’s new web accessibility requirements, which states have about one year to comply with before they become enforceable.

“You can’t do it all with automated tests,” Gifford said of his use of Google Lighthouse. “You never will, but this is sort of like if you’re running a triathlon, this will tell you what the score is for how fast your time was for swimming, and it doesn’t tell you anything about how well you’ve run the the marathon or run the cycling course on this. To meet the minimum requirements for accessibility, this has to be 100%. And it’s not.”

Regarding the scores, Gifford said he hopes to bring a sense of urgency to lower-ranking states and encourage more government officials to think about accessibility.

“We could start to provide some incentives for for governments to be able to to start investing in accessibility. Because historically, all this stuff has been kind of invisible,” Gifford said. “The governments themselves don’t necessarily know how accessible they are, certainly the citizens of that state don’t know how accessible they are. They just know if they run into a problem with a particular site. There’s no way to provide a state level assessment of accessibility before I ran this test, or before I ran these these queries that was able to highlight some of this information.”