Not waiting for the feds, Ohio representatives approve rural broadband fund

With no promise of additional federal funding for rural broadband forthcoming, states like Ohio are moving on state-led initiatives to fill wide service gaps in sparsely populated communities.

The Ohio House of Representatives easily passed a bill on Wednesday that would establish a $50 million annual grant program for broadband expansion throughout the state. Approximately 300,000 households lack access to broadband in the state, according to nonprofit advocacy group Connect Ohio — a microcosm of the 23 million rural residents who lack broadband access nationally.

Introduced by Republican Rep. Ryan Smith and Democratic Rep. Jack Cera, the bill received strong bipartisan support that signals the internet’s elevated status among state government’s competing infrastructure priorities.

“Broadband is no longer a luxury,” said Smith, chairman of the House Finance Committee, upon the bill’s passage. “It is just as important as roads and bridges.”

If made law, new funding would be drawn from bond revenue of the Ohio Third Frontier, a technology-based economic development initiative run by the state’s Development Services Agency.

The bill now heads to the Republican-controlled Senate, where it must pass by the end of the year to become law. Despite the bill’s support from politicians of all stripes and community advocates like Connect Ohio Founder Stuart Johnson, who called the bill “absolutely critical” to improving the state’s healthcare, government services, education and economy, passage is no guarantee of widespread connectivity.

The FCC’s Connect America Fund Phase II Auction will provide $1.98 billion to communities for rural broadband expansion within the next 10 years, but CAF funding has traditionally landed in the accounts of large internet companies, providing no guarantee that a given rural community will become a beneficiary of the program. Broadband deployment is expensive, particularly in rural Ohio, where low-population towns nestled in Appalachian forests do not constitute a business incentive for the likes of telecom giants like AT&T and Charter Communications, even when subsidized by the federal government.

And while no broadband advocate is likely to turn down the chance at fresh dollars to connect residents to what is considered in their circles to be the most important invention in recent human history, a few, like Christopher Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, say some of the bill’s provisions, or lack thereof, are worrying.

“I’m really disappointed they didn’t explicitly disallow satellite as a broadband service,” Mitchell said.

Satellite internet service can reach FCC’s definition of high-speed internet — 25 Mbps download/3 Mbps upload — but it typically comes with other restrictions like daily bandwidth caps, a relatively high cost, and high latency that hinders many applications and services. It’s technically broadband, but not the cheap and abundant utility that most have in mind.

“Broadband is not just about speed,” Mitchell said. “It’s about a lot of other characteristics that sometimes people take for granted until they use satellite and realize speed is not everything.”

Mitchell also says Ohio’s “right of first refusal” provision “lacks teeth.” Right of first refusal allows a regional service provider to block new infrastructure investment by another entity if the provider promises to do its own upgrade in the area instead. Ohio’s provision, however, does not require that the upgrade match the speed or cost of its competitor. If, for example, AT&T wanted to shut down a proposed gigabit network that would draw on federal funds, it could propose a much-slower DSL upgrade instead. Their theoretically inferior project would meet the right of first refusal requirement and stop their competition.

Colorado’s right of first refusal clause, which requires a network speed match at equal or less project cost, is more fair, said Mitchell, still sounding disappointed.

“The thing that just gets me is I’ve been having these debates for 10 years,” Mitchell said. “In 2008, it’s understandable if ISPs hadn’t yet gotten around the building the networks. It’s 2018. These big companies have had all the opportunities they need.”

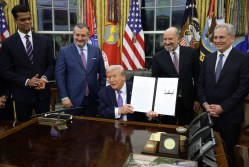

New sources of federal funding are scarce. President Donald Trump’s giant infrastructure plan, which might have included broadband funding among its $50 billion in rural infrastructure allocations, stalled last month as a Republican-controlled Congress struggled to find ways to fund the 10-year commitment without raising taxes.