Maryland becomes first state to adopt Open Law Library for its legal code

Maryland Gov. Wes Moore last week announced the state has adopted a new online platform to publish its regulations, an expansive set of rules governing seemingly everything, from sanitation rules for barbers to the technical data packages used to test voting systems.

The upgrade makes Maryland the first state to adopt software from the Open Law Library, a nonprofit that’s made it its mission to make legal codes more accessible to the public and easier for governments to update. Open Law Library is already used by major cities, including Baltimore and Washington, D.C., along with about a dozen tribal governments, but it took a decade of persistence before the group managed to convince a state to migrate over.

“I had no idea how hard it was going to be,” said David Greisen, Open Law Library’s founding director and chief executive. “I knew how technically difficult it was going to be, but the building an organization around the technology … I hadn’t fully understood the scope.”

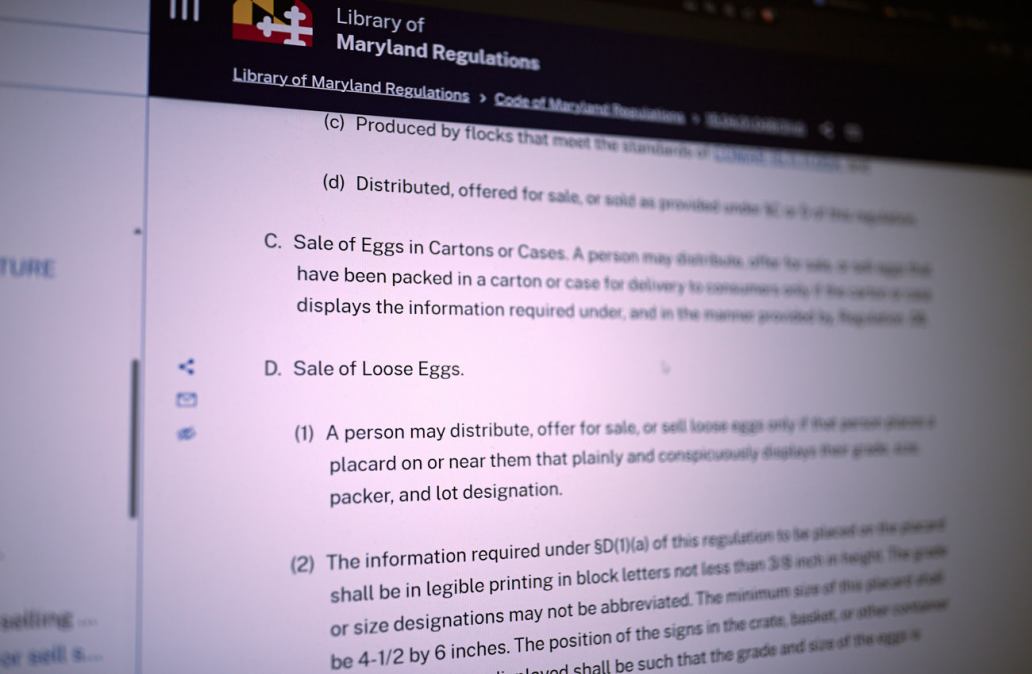

As is typical for a state, Maryland’s legal code was already available online. The state’s Division of State Documents publishes on its website the Code of Maryland Regulations, known lovingly to legal professionals and state workers as COMAR. Are you allowed to sell loose eggs in Maryland? COMAR has the answer. (Only if the seller “places a placard on or near them that plainly and conspicuously displays their grade, size, packer, and lot designation.”) Before recycling fees on tires can be assessed, “tire” must first be defined. It’s defined in COMAR. (Maryland’s legal code has it that a tire is a “continuous rubber or similar material or synthetic material which is pneumatically designed or intended to cover or encircle a wheel” for motor vehicles, trailers, farming implements or machinery. As you likely suspected.)

Such facts can present as tedious, but state legal codes are of great consequence. They contain criminal sentencing guidelines. They establish rules for small businesses and child care centers. Such details can determine the trajectories of many lives. Greisen has over the years pointed out that the critical role that laws play in America’s particular form of government is at odds with how difficult it is for people to access those laws. He created Open Law Library with a vision of making legal code as easy to navigate as pulling up a fact on Wikipedia.

“I think of it as shoring up the foundations really of our democracy,” Greisen said. “People have to trust the laws and know what the laws are in order for democracy to function, and we’re trying to help governments do that better and faster.”

Maryland’s old platform for publishing laws appears to work fine. Users can click through a hyperlinked hierarchy of regulations and find the latest text for COMAR, which is updated every two weeks. But those most familiar with the old system said it was poorly designed, aggravating to update and lacking in essential features, like an effective search function.

“In the past, I think they did the bare minimum,” Michael Lore, Maryland’s deputy secretary of state, said of the old platform’s search.

Maryland’s legal code is highly active, and alterations, Lore said, which can be as large as an entire volume or as small as a single word, occur constantly. Busy revision periods can bring as many as 500 changes. Updating COMAR in the old system, which is based on Microsoft Sharepoint, was a matter of updating Word documents, ASPX files and PDFs in as many as five locations — “We had to make sure everything was edited correctly and sometimes we’d go through and things wouldn’t stick,” Lore said.

Officials involved in the upgrade said that over many years they never once missed updating COMAR for a two-week deadline, but that there have been some close calls, and that the system’s scatterbrained design didn’t help. Susan Lee, Maryland’s secretary of state, called the old system “woefully inadequate,” Lore relayed. Open Law Library, conversely, relies on a “single source of truth.” State agencies need only update their legal code once, on Github, and the changes will propagate to the appropriate locations.

Driven by its mission, rather than profit, and having been steadily enhanced with new features over the last decade as the project has gained input from a growing base of local government users, Open Law Library is a love letter to efficient design, user experience and the law. Its plain interface doesn’t shout innovation, but it succeeds in all the ways readers might care. It’s lightning fast, it’s intuitive and it’s rich with unobtrusive features that could only have been conceived by a group of people with a perverse love of legal code.

It is, for instance, easy to compare Maryland’s current regulations with historical archived versions, a task that in the past required manual searching. “White papers” published on the Open Law Library website chronicle the software’s evolution, like the addition of a feature in its drafting tool that notifies users when they’ve violated accessibility rules, or a feature that allows attorneys to privately annotate sections of legal code.

“The new website is just so much easier to use,” said Clare Bayley, a senior product manager at Maryland’s technology department, who worked with the secretary of state’s office and state documents office to understand the extent of their annoyance with the old platform. “The amount of manual Word doc manipulation and duplication of effort in the [previous] system is, like, extremely high. And they work very long hours at tasks that computers are good at.”

Not counting attachments and PDFs, COMAR exceeded 22,000 Word documents. Getting them into the new system, Bayley said, was a matter of ensuring everything was machine readable “and then double checking and double checking and double checking, because you can’t have mistakes in the law.”

Marcy Jacobs, Maryland’s chief digital experience officer, said the project’s success can be owed to an approach taken by the technology department, which did not “go off in a corner with OLL and say here’s your new regulations site” but worked closely with agencies to understand their processes and improve them.

“That’s not something the Department of IT has really done before,” Jacobs said.

The official version of Maryland’s legal code remains the physical printed version, but perhaps in recognition of the digital world’s growing influence — and how an incident could erode trust in the state — both Open Law Library and Maryland’s state government made security a priority. Open Law Library relies on security software developed at New York University called The Archive Framework, which is derived from The Update Framework, or TUF, technology that is used widely, including by companies like Amazon and Google, to prevent bad actors from interfering with software updates.

Justin Cappos, an NYU computer science professor who developed TUF, said he met Greisen about five years ago at a TUF project meeting. Greisen began asking him questions about the software, apparently interested in the best security possible for his platform.

“People who are worried about a nation-state attacking them, TUF is what they use,” Cappos said. “We kind of have carved out this market for how to do this if you really don’t want to have a bad day if you get hacked.”

Also involved in Cappos’ security work, which is funded by a National Science Foundation grant aimed at hardening the defense of supply chains, is BJ Ard, an associate law professor and associate dean for research and faculty development at the University of Wisconsin Law School. Ard said that new security concerns are inevitable as digital access improves.

“In the print era, when there was an official legal publication, there was a certain trustworthiness to it because we had a physical artifact that would have been difficult to alter on such a scale you would be able to change or corrupt what the law said,” Ard said. “That came with the cost of limited access. Most of these books were only in certain law libraries or at certain law firms or in various government offices, but the trustworthiness was there.”

(Lore, Maryland’s deputy secretary of state, said that, “believe it or not,” some people are still buying physical copies of COMAR, and that those sales remain part of the office’s revenue model.)

But the technologists behind Open Law Library aren’t thinking only of maintaining the integrity of legal code into next year or even the next decade. Cappos said they’re working on a project that will ensure the secure verification of laws across centuries, and that “that is an entirely different sort of thing that requires us to do a lot more work.”

“That may sound silly,” Greisen wrote in an email when asked about the project, “but the oldest law currently codified on our platform is very nearly there.” He linked to a law of the United Kingdom archived in the District of Columbia legal code. A scanned document from the year 1267, which appears to be written in Old English, advises on matters of freeholders, townships and which types of manslaughter are also considered murder. Loose eggs, at least on that page, are not mentioned.