State and local governments should prepare for changes to CISA, cyber experts say

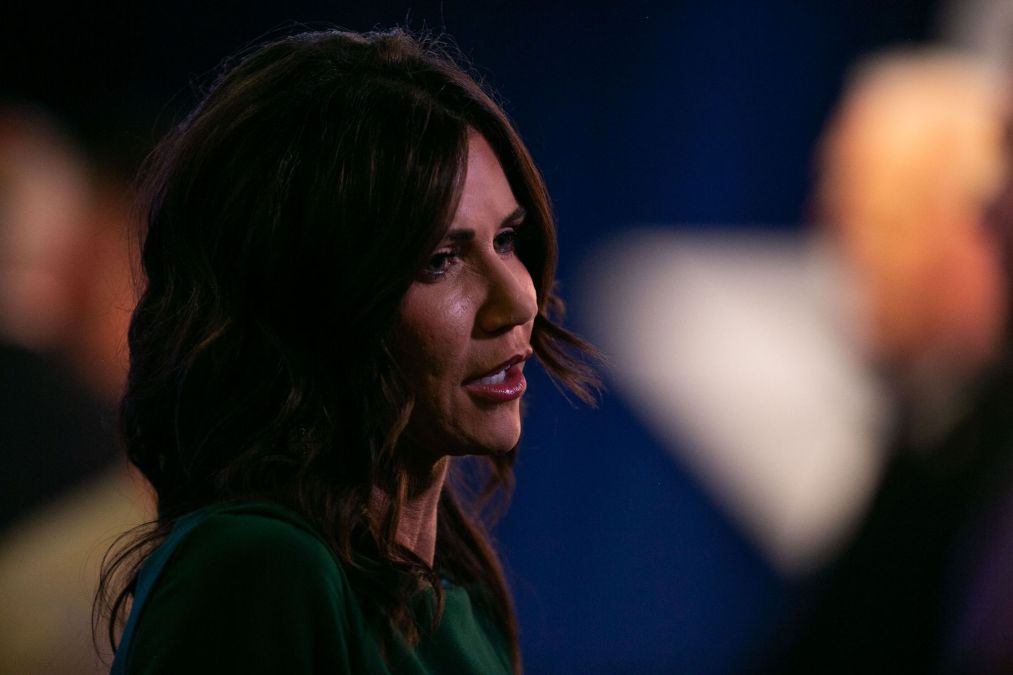

Cybersecurity experts told StateScoop that state and local governments should brace themselves for changes to the Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency under Kristi Noem, former governor of South Dakota, who was sworn in last weekend as the 8th secretary of the Department of Homeland Security.

During her confirmation hearing a week earlier, Noem said she believes the security agency has gone “off-mission,” focusing on tasks other than protecting critical infrastructure, and that she intends to make the CISA “smaller and more nimble.”

“CISA’s gotten far off-mission,” Noem told the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs committee during her confirmation hearing on Jan. 17. “They’re using their resources in ways that was never intended. The misinformation and disinformation that they have stuck their toe into and meddled with should be refocused back onto what their job is.”

Misinformation became a major grievance of the Trump during the 2020 presidential election and over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many conservatives claimed their free speech, particularly on social media, was being censored by federal agencies, like CISA.

Pamela Smith, CEO of Verified Voting, an organization that studies how technology impacts the administration of U.S. elections, said the loss of verified information monitoring may impact election security, which is managed by local government agencies.

“CISA has a coordinating function. Their ability to monitor for mis- and disinformation campaigns that may be coming from outside the country, is probably greater than other agencies,” Smith told StateScoop in a recent interview. “It puts more pressure on the entities that have to deal with this, the election officials themselves, to monitor and quickly provide information.”

“Election security is kind of newer to the family of critical infrastructure,” Smith explained.

The Department of Homeland Security, which houses CISA, designated elections as part of critical infrastructure in 2017, shortly after the 2016 presidential election, when evidence of foreign interference began to surface.

“Most counties are not large and robustly funded, and election ends are kind of far down the list, after things like, you know, fire, police and other kinds of things that you might spend money on,” said Smith. “So having free support and tools and information and training from CISA has been crucially important.”

Smith said that while there’s a difference between being a governor and the secretary of state, who helps manage local and statewide elections, Noem’s experience as a governor and working with state election officials should give her sense of urgency about the issue.

“Even at the gubernatorial level, your state has a CIO, you have your security bodies, entities that help secure state systems,” Smith said. “You would think that that would lend itself to that kind of understanding.”

Concern for CISA’s cyber grants

Noem’s ascension to head the Department of Homeland Security comes as critical infrastructure — including ports, schools, health care agencies and water treatment facilities, often managed by local municipalities with limited funding — faces increasingly sophisticated cybersecurity threats, according to CISA.

“What CISA should be doing is helping those small entities, those schools, those local city governments, the state governments, and the small businesses that are critical infrastructure that don’t have the resources to stay on top of the critical protections that they need to enact,” Noem said during her confirmation hearing.

Noem also told senators that CISA’s current funding initiatives, including the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, will be “looked at to see what we can do to make sure that they’re actually fulfilling the mission to which they were established.”

Part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the four-year cyber grant program, now in its third year, set aside roughly $1 billion to strengthen state and local cybersecurity efforts, such as incident planning and exercises, hiring cyber personnel, and improving security of its digital services. States are required to distribute 80% of the grant funds to their local governments.

The White House did not respond to requests for clarification about what will happen to the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program. Smith said she thinks halting the program would be “extremely unfortunate” and “dangerous.”

“Not nearly enough money gets spent on elections and elections infrastructure, and anytime you’re removing some of that, it’s harmful,” she said.

South Dakota was the only state not to participate in the cyber grant program after Florida opted in during its second year. Noem defended the decision, saying she would have needed to hire more cybersecurity personnel and “grow my state government” to fulfill the grant’s requirements.

“The administration costs of it would’ve been much more than what it been able to facilitate at the local level. And our state was already proactively helping these individuals that needed the resources to secure their systems,” Noem told senators.

A cybersecurity ‘cornerstone’

Jorge Lllano, a former chief information security officer for the New York City Housing Authority, told StateScoop he’s concerned about potential budget cuts at CISA, which he said could affect IT infrastructure of local agencies.

“These IT infrastructures are at risk because they’re old and outdated end of life, and they still need to be remediated and replaced,” Llano said. “Without that funding, this equipment could still stay accessible on networks, and these systems continue to have vulnerabilities and risks that could be exploded by threat actors.”

Llano, who now works for the cybersecurity firm NuHarbor, said that local agencies like NYCHA, often require people to submit sensitive information, such as Social Security numbers, previous addresses and job forms to access public housing benefits or other government services.

He said threat intelligence sharing, one of CISA’s major functions, is important and that state governments should prepare for potential funding cuts by identifying high-risk systems and conducting more tabletop exercises.

“Threat intelligence sharing could allow for more efficient and robust defenses against cyber threats, so I’m hoping that Kristi Noem, DHS and CISA are doing that,” Llano said.

Erik Avakian, Pennsylvania’s former CISO, agreed.

“Information sharing in cybersecurity is extremely report important, almost like a cornerstone, [because] we need timely and accurate intelligence that are getting to the right people at the right times,” said Avakian, now a technical counselor for Info-Tech Research Group.

Avakian said that the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center, which is run by the New York nonprofit Center for Internet Security, and that receives funding from the Department of Homeland Security, has long-term relationships with state and local agencies. He said it has low turnover and that it complements CISA’s services.

“I know many local governments, cities, schools, townships that are that are members of MS-ISAC that rely on them for the services they provide, so it’s really important that funding does continue,” Avakian said.

Avakian also said he was confused by the politicization of cybersecurity.

“Cyber is not political,” he said. “Once we politicize it, it brings in other folks within the administrations that are calling different shots. The chief information security officer in the organization should understand what to do when it comes to cyber, but if there’s directions coming from the top in that government, it becomes difficult.”

Self-sufficient ‘whole-of-state’

Avakian, who served as Pennsylvania’s CISO for more than 10 years, argued that current cyber officers should use this moment to rethink how cybersecurity is funded within their states, a view echoed by the National Association of State Chief Information Officers.

“I don’t like to say the word ‘waste,’ because there’s no efforts that are wasted,” he said. “I think there’s an opportunity to really refocus on the mission and de-politicize cybersecurity.”

Avakian urged CISOs to demonstrate the value of their cybersecurity programs to lawmakers in order to secure ongoing support, instead of relying on funding from federal agencies, where priorities may change under different administrations.

“We should have money allocated in our state budgets, maybe even having a separate line item for cybersecurity,” said Avakian.

Avakian also stressed the importance for state and local agencies to share more security services under the “whole of state” approach to cybersecurity, in which multiple levels of government, educational institutions and private sector organizations work together to strengthen cybersecurity capabilities.

“We all go to the airport, we all go through the machine. We take off our shoes, they go and then they scan us as we go through the machine, And so these are examples of consistent processes and tooling services,” Avakian said. “But if we went through one airport and they just let us through, we probably wonder, are we really secure?”